The Practice of English Language Teaching (CELTA course study material #1) By Jeremy Harmer

These are my notes for the CELTA course and one of the suggested reading, found at archive.org. Definitely a skimmable post, since it’s nearly an edit of the edition with exception to not listing all of the Figures given or some of the links for no longer being active, but still referenced.

This is also going to be a jankier edit, since I have yet to find a writing platform which will allow for simple copy paste with jpg’s and tabbed space, and ruining the alignment of the examples provided. Due to learning about this nearly at the end of my notes, I’ll be editing to skeleton quality.

Intro. This edition is focused on context sensitive teaching more than the previous editions. Different Learning Contexts listed in Ch 7. Native speaker and non native speaker teacher issues listed in Ch 6.

CH1

For some people, the rise of English speaking can cause unease or celebrating. English language’s future superiority, and growth could be halted. English’s status as one language being challenged by different Englishes used around the world.

How English became to be used so widespread cause by colonial history, economics, info exchange, travel, pop culture.

Colonial history - imposing English as the one language of admin helped maintain colonizers power. British colonial ambitions played a large role in how far reaching its become.

Econ - the survival of the establishment of the language and growth comes from economic power. US being an Econ power was a large factor in English being spread further through global commerce. One example being from Sri Lankan English which gets more popular due to the work with tech asst and call centers.

Info exchange - currently English dominated through the internet which is listed more in CH11, but how this could also change despite being dominated by English from US internet origin.

Travel - dominant in tourism, it also is preferred language in air traffic control in many countries and sea travel communication.

Pop culture - Pop music in English, or in TV and movies, despite having Bollywood be much larger of a producer, English speaking countries including UK CAN AU US promote their movies as well for attracting those in Asia as a choice for a study destination.

Speakers of World English makes one more capable of dealing with wider range of English varieties than those with native speaker attitudes and competence in regards to outsourced call centers making anyone who can’t deal with Punjabi English or the like communicatively deficient. So instead of speaker proficiency being focused on, it’s high and low proficiency users.

English as Lingua Franca (ELF) - 2 people using English as a 2nd language. These convos have characteristics including:

non use of 3rd person present simple tense-s (She look very sad)

interchangeable use of relative pronouns who and which (a book who, a person which)

omitting definite and indefinite articles where it’s obligatory in native speaker English, and insertion where they do not occur in native English

Use of all-purpose tag question such as, isn’t it? Or, no? Instead of, shouldn’t they (They should arrive soon, isn’t it?)

Increase redundancy by adding prepositions (We have to study about… and, Can we discuss about…?), or by increasing explicitness (black color, versus, black, and, How long time? Versus, How long?)

Heavy reliance on certain verbs of high semantic generality, such as, do, have, make, put, take

Pluralization of nouns which are considered uncountable in native speaker English (informations, staffs, advices)

Use of, that clauses instead of infinitive constructions (I want that we discuss about my dissertation)

“…the evidence suggests that non-native speakers are not conforming to a native English standard.” One other difference, is non-native speakers are more accommodating to things which shouldn’t be done, and tend to help each other in a cooperative way moreso than a native English speaker is when talking with 2nd language speakers.

This makes non native speakers better at ELF communicating than native speakers. So from the other side, the supposed things ELF speakers shouldn’t do, these expert speakers due to being successful communicators have just as much right to say what is correct as native speakers do.

Also, due to knowing the info currently about ELF it should influence what kind of English to teach.

Learners need to learn about Englishes regarding their similarities and differences, issues including intelligibility, strong links between language and identity, etc. For pronunciation, focus on core phonology. Avoid idioms, since ELF speakers don’t use them. This is case by case basis depending on the learners wants.

When becoming more advanced, the variety of prestige may include metaphor and idiom as long as it’s not too culture-specific. More importantly is exposure to World English. As they get more advanced they should become aware of different Englishes without swamping them with diversity, but guide in an appreciation of the global English phenomenon.

CH2

Noting the differences on how we speak over letter-writing and text messaging with abbreviations, short-hand, or formality.

Form and meaning can sometimes be different. Example being, a student smoking in a non smoking area. The teacher informs the student, who may know already and only thanks the teacher due to being caught. The formation of the teacher letting his boss know the same may have come out differently due to respect for his boss’ title.

Meanwhile, the present continuous, Future: I’m arriving at 8.

Present continuous format (aka progressive) refers to a temporary transient present reality. Look at John. He’s laughing his head off at something.

A 3rd meaning of present continuous is: The problem with John is he’s always laughing when he should be serious, describing the habitual and not temporary action.

Context (situation) and co-text (lexis and grammar surrounding the form: 8 o clock, Look at John, etc) involves resolve in ambiguity. This helps make decisions of what forms to teach and meanings to teach them with for syllabus planning.

Multiple ways of inviting someone to cinema is one example of performative verbs.

6 variables which govern how to choose how to speak:

Setting: If in a library or a night club. Office and work environment will have different forms of speech expected.

Participants - Speaking with a superior or writing to friends, family or colleagues

Gender - men and women use language different when addressing either members from opposite or same sex. Especially in convos, women more concessive language than men and talk less in mixed-sex chat.

Channel - differences between spoken and written language. Spoken language is affected by situation we are in. If speaking face to face or telephone, with a mic in front of a crowd or unseen in a lecture hall. The writing channel (format) also affects writing.

Topic - choice of topic affects lexical and grammatical choices. If talking about a wedding would be different than the speech in convo about particle physics. Or childbirth lexical phrases compared to football. Topic-based vocabulary is a feature of register or choice, made about what language to employ.

Tone - A features of the register in which something is said or written with a tone. Like formality or informality. Politeness or impoliteness. An example , a women’s mag talks of make-up, but teen mags call it “slap”. Or using high pitch and exaggerated pitch movement often more polite than flat monotone speech if asking to repeat something. This is the type of scenarios which influence choice of speech. When teaching this, it’s important to draw the student’s attention to these issues. Like- ask why a speaker uses particular words or expressions in a specific situation. Ask our students to prepare for a speaking activity by assembling the necessary topic words and phrases. Discuss the sort of language appropriate for an office situation when talking with a superior and whether the sex of the superior makes a difference. Important for students to be aware language is a social construct as much as a mental ability.

Discourse organisation has to be organized or conducted in a certain way to succeed. In written English this calls for both coherence and cohesion. For a text to be coherent it needs to be in the right order - and at the least, make sense.

An example is putting sentences from Frank McCourt text, Teacher Man out of order and the paragraph becomes incoherent. When read in proper order, the internal logic becomes clear. Regardless of a coherence to a text, though, doesn’t work unless it has internal cohesion. Each element of the text must stick to each other successfully to help navigate our way around the discourse.

One way to do this is with lexical cohesion, and a way of ensuring it is through the repetition of words and phrases (ie, on the first day, on the second day, high school repeated, fired repeated.). Interrelated words and meanings can also be used (or lexical set chains) to bind text together (teaching, boy, high school, classrooms) from the paragraph.

Grammatical cohesion is achieved multiple ways, one most common is the concept of anaphoric reference, which is using pronouns, to refer back to things already mentioned, like in example: his refers back to Frank McCourt, and it refers back to his book Angela’s Ashes: Frank McCourt first emerged on the literary scene with his book Angela’s Ashes, a memoir of a childhood lived in poverty. It became an instant classic.

A similar cohesive technique is using substitution, using a phrase to refer to something we have already written (The example is the last 2 sentences refer to how long he’d lasted with the job teaching which was over 30 years). Grammatical cohesion is also achieved by tense agreement, since if the writer constantly changes tense it will make the text difficult to follow. Writers also use linkers, like and, also, moreover, however, etc which is also present in spoken language. Verbal shorthand: Another round? Might as well. These two sentences referring to whether two people want a second round of drinks, and they may as well have the second round of drinks.

To be successful with conversational discourse, participants must know how to organize events in it, like when to take turns and interrupt, and show when they want to continue speaking, or happy to give the floor to someone else. In order to be successful, they need to use discourse markers effectively. These are the spoken equivalent to linkers, like “anyways, moving on, right”, which begins new thread of discussion or ends them. Ok? Right? Encourages listeners agreement, and yeah, but, and ok, said with doubtful intonation, indicates doubt or disagreement.

Lastly for convos to proceed successfully, participants need to be sure they’re playing the game according to the same rules. So if someone asks a question, the second speaker is expected to answer, which shows cooperation at the heart of cooperative principle, which makes the speakers contribution as informative as required, the contribution is true, relevant, and avoids obscurity and ambiguity, and be brief and orderly. These may not always be present, frequently excusing ourselves for disobeying maxims with phrases like, At the risk of simplifying things, or I may be wrong but I think…

Another factor of successful spoken discourse is intonation.

One reason people successfully communicate especially in writing is understanding genre. A popular description for ESP teachers is to say genre is a type of written organisation or layout (advert, a letter, poem, mag article etc) instantly recognized for what it is by members of a discourse community, any group of people who share the same language, customs, and norms.

Advertising has many variations. Examples show sub-genres of advertisements: online job advert/theatre listing/relationships: called, ‘soulmates’ in text. Despite the differences in adverts, they show a characteristic which is written for the discourse community to recognize instantly the meaning of them and what they are. Further detail about each advert is given and the shorthand which each discourse community would be able to decipher for reading these ads more than once. So, when teaching how to write letters, send emails, or make oral presentations, we want them to be aware of the genre norms and constraints which are involved in these events, but not to imitate one type, but to be aware of possibilities and opportunities by showing students a variety of texts within a genre rather than asking for imitation of one type, more detail in CH19. Whatever text is constructed or co-constructed, like a convo where speakers together make the convo work, the sentences and utterances we use are combos of grammar, morphology, lexis, and in the case of speaking, sounds.

Grammar - a previously used sentence: I will arrive at around eight o’clock, for its success, must have the words in the write order. Example: I arrive will at eight o clock around, showing incorrect utterance, due to auxiliary verbs (will) always come before main verbs (arrive) in affirming sentences. Same with the modifying adverb, around, come after the time adverbial, since it’s its correct position is before it.

Syntax is the system of rules which shows what can come before and which order different elements can go in.

The formation of a word is morphology - when it can be changed to indicate time. Example: Arrive(d) (ing)

Transitive (take an object) Intransitive (doesn’t take an object) or both, occurs with verbs like ‘herd’ - to herd sheep is transitive, it takes an object. The verb open, can be either transitive or intransitive. Example: a dentist says, open your mouth (transitive), or the dentist’s surgery opens at eight o clock (intransitive).

Verbs are also good examples to trigger grammatical behavior words around them, for instance, like, triggers the use of either -ing form in verbs which follow it (I like listening to music) or the use of to + infinitive (I like to listen to music), but in British English, like can’t be followed by that + a sentence (we can’t say *she likes that she sails*). The verb, tell, triggers the use of a direct object, and if there’s a following verb, the construction, to + infinitive (she told me to arrive on time), but, say triggers, that + a clause construction (she said that I should arrive on time).

Students need to consciously or unconsciously understand this and the implications. Problems stem from when rules are complex or difficult to perceive. Language awareness is a great responsibility to help students develop and spot grammatical patterns and behavior for themselves. More in CH3C

Lexis - is the vocab of a language. Word meaning, how words extend through metaphor and idiom, and combine to form collocations (frequently occurring combos) and longer lexical phrases which are a major feature of all languages.

https://www.lextutor.ca - pronunciation and how to use it in a sentence, along with most common ways of usage.

Sometimes knowing the opposite of a word, helps make clear what meaning the sentence is referring to, since some words have more than one meaning (polysemous), but a particular meaning could be more common.

Synonyms can show similar or same meaning words but still require knowledge of when to use them.

Hyponymy is sub categories of a type like, fruit have sub choices with types: lemon, banana, orange, apple, etc. A diagram follows with ‘food’ being the main category, breaking down into, meat, fish, fruit, and cereals, fruit breaks down to the types of fruit mentioned, called superordinates aka hyponyms

Words can also have different connotations, depending on context often. Smart can be a positive meaning for intelligence or it could suggest someone’s devious or self-seeking.

Or words can have meaning stretched, when green can mean naive or new, and black can mean cross

Metaphor for words can also be described by using the word tumble having to do with prices going dramatically down. When certain phrases are known by speakers, they become idioms, a common expression: He has bitten off more than he can chew.

Phrasal verb: take off, put up with - made up of 2 or more words with one meaning unit, Aka lexemes

Single words are also meaning units, but it’s important to recognize both.

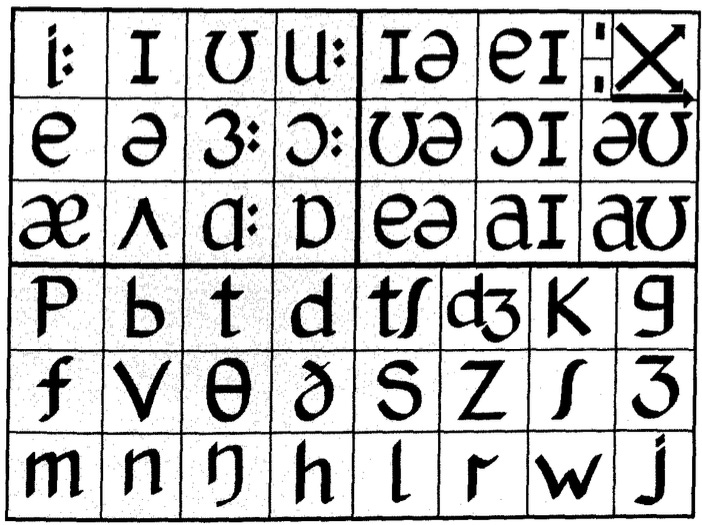

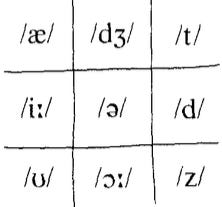

Pronunciation is focused on in CH15

Pronunciation issues: pitch, intonation, individual sounds, sounds and spelling, and stress.

Intonation is used to show the grammar of what we’re saying. Tone unit is any collection of sounds/words with one nucleus - the falling tone indicates tone unit is a statement. Falling tones are sometimes called proclaiming tones and used when giving new info or adding to what’s been said. Fall-rise tones are referring tones, when referring to info we want to share or to check info. Figuring out pitch direction is discussed in CH15

How to position mouth or tongue when saying certain letters can be important.

Spelling doesn’t automatically mean something will sound the same. Different spelling can give the same sound.

Elision can take place of the previous sound. I can’t dance. The t disappears because of the d sound after.

Stress on a word can be different to type of English, like British and American.

Sometimes adopting mannerisms can show one speaker agrees with the other, but if done consciously can seem like mockery of another’s action.

Using video material to show gesture and posture will be mentioned in CH18

Verbal speech can be much more short direct question answer as opposed to written being more formal.

Chat online is like speaking, a lecture is more like writing.

CH3

How children learn language from parents when young as opposed to learners in the classroom setting.

Some people can pick up a second language without lessons, but mastery isn’t usual from this way, so usually learners choose the classroom, despite if a learner wanted a similar experience to how children learn, it’d be best to immerse by living in the community the language is spoken.

Harold Palmer had interest in comparing “spontaneous” learners over “studial” one played into the other, spontaneous, going into the community was good for acquiring the start to the language, and studial was developing literacy.

Language acquired subconsciously, anxiety free, is more easily available in spontaneous convo, but when it’s learned, it isn’t available for spontaneous use. So, learnt language is best to “monitor” spontaneous communication.

Incentive also drives learning in a positive or negative way and through conditioning will refine the words to be more specific to their needs.

Having students do drills of sentences with positive reinforcement or incentives is also criticized but has its benefits in behaviorism, but is simplistic in it’s theory since the link to audio lingual method of learning makes contribution to applied language settings.

Learning is from the result of unhampered participation in a meaningful setting.

Students were given tasks, like request for library books or interview people, which made them speak or read, something teachers couldn’t advise or correct.

Students also participated in communication games where the objective is to complete a task with the language at their disposal. Ex. Putting objects in the same order only by direction, or drawing the same picture by description and not being allowed to look at the picture.

Allow students to say what they think and feel allows a safe environment to develop more language without feeling threatened.

Focus on form grows through use of communicative tasks.

**TASK PERFORMANCE INCREASES LEARNER AWARENESS OF TARGET STRUCTURE AND IMPROVE ACCURACY IN USE, PROVIDES MEANING FOCUSED COMPREHENSION, AND PRODUCTION OF TARGET LANGUAGE

Students acquire language best when they know it will help them communicate in certain situations which serve their interests, which is hard to anticipate or make lessons for, so being more about general ways of multi-use environment language.

Repetition also is important if the student is applying what it means as they use it. Repeated encounters with the language helps set it in the learners mind.

The process of exploration with language will allow learners to find true understanding.

Exposing students to examples of present perfect tense and allow them under guidance to work out how to use it. Providing a word and having student look it up in a dictionary and find collocations on their own. Have students look at transcripts instead of telling them about spoken grammar and have them reach their own conclusions to how it differs from written grammar. This provokes “noticing for the learner”.

Keeping a humanist environment, where it’s supportive rather than alienating in the learning process will allow for the student to retain what’s learned.

CH4 Popular methodology

Method is the practical realization of an Approach, which include procedures and techniques of the types of activities, roles of teacher and students and the material which will be helpful.

Have students murmur a word to themselves to get their mouth formations and tongues around it.

Audiolingual drills become popular so the student constantly learns to substitute words in a controlled drill.

This will promote habit formation thru constant repetition of correct utterances and supported by positive reinforcement.

PPP - Presentation, practice, production

Presentation - the teacher shows students a picture and asks whether the people in it are at work or on holiday.

Practice - the teacher has students repeat a sentence, then have students answer individually and corrects mistakes when heard, then returns to modeling more sentences from a picture. Each time getting everyone and single repetition when necessary. This enables a cue-response drill where the asking can be more free since the student understands the answer prompted. Sometimes the teacher will pair the students to practice the sentences before listening to a couple examples to be sure the learning is effective.

Production - “immediate creativity” - students are asked to use the new language in sentences of their own creation. Ex. What a family member would be doing right now.

Boomerang procedure follows more task based or deep end approach. The order is EAS, and the teacher gets the students engaged before asking them to do something like a written task a communication game or a role play. Based on what happens there, the students then after the activity finishes study some aspect of language which they lacked or which they used incorrectly.

Patchwork lesson are different from the previous two procedures, for example, engaged students are encouraged to activate their knowledge before studying one and then another language element, and then returning to more activating tasks, after which the teacher re-engages them before doing some more study, etc. What the Engage/Study/Activate trilogy has tried to capture is the fact PPP is just a tool used by teachers for one of their many possible purposed.

PPP is extremely useful in focus on forms lesson esp at lower levels but is irrelevant in a skills lesson where focus on form may occur as a result of something students hear or read. It’s useful to teach grammar points such as the use of can and can’t but has little place when students are analyzing their own language use after doing a communicative task.

Issue with PPP is it’s TEACHER CENTERED RATHER THAN STUDENT but can be useful in a focus on forms lesson for lower levels but irrelevant for skills lessons. It’s useful in teaching grammar points like the use of can and can’t, but not for analyzing the students own language use after doing a communicative task.

The Silent Way - teacher doesn’t speak and through pointing indicates words which should be spoken and moving on to the next when correct pronunciation is given rather than verbal reinforcement.

This gives the student responsibility for their learning and the teacher can do the job of organizing this.

CLT Communicative Language Teaching or the Communicative approach allows for teachers to encourage people to invite, apologize, agree and disagree, along with making sure they could use the past perfect or second conditional. Typical tasks for students involve they in real or realistic communication where they achieve the communicative task they’re performing is as important as their language use. Role-play and simulation are popular, simulating a tv show or a scene at an airport. Or the students solve a puzzle and can only do so by sharing info. Sometimes students are made to write a poem or construct a story together.

Certain practices may suit certain students better, so being flexible with teaching practices according to the students culture and interest may eventually make the teaching process easier.

For CHINESE STUDENTS repetitive listening to tapes of language was bargained to being able to do it whenever they wanted, but they would have to do ‘gist understanding’ with guided questions and slowly reduce the repetition tapes to show progress on their listening skills.

WHAT STUDENTS NEED AND SHOULD BE OFFERED?

Affect: students learn better when engaged with what’s happening.

Input: students need constant exposure to the language, by reading or the way the teacher talks to them. Focus on form, esp at lower levels, on language forms is vital for successful learning

Output: students need a chance to activate language knowledge through meaning-focused tasks. Using the language to speak or write or reading, or listen for meaning.

Cognitive effort: students should be encouraged to think about language as they work with it which aids retention. Encourage doing some of the work themselves and sicker how language works rather than being given the info about language construction handed to them.

Grammar and lexis: lexis is as important as grammar, how words combine together and behave semantically and grammatically

How, why, and where: the way it’s done isn’t dependent on a method, but on why or where we’re teaching. What’s meant to be achieved, with who, and what context? Analyse the features and choose from procedures and techniques at our command which best fit situation we’re in. At all levels and stages of teaching we should be able to say clearly why we are doing what we are doing.

CH5

Age - Students age will determine how and what to teach. Age gives needs, competence levels, and cognitive skill differences. Children learn thru play, and adults use greater abstract thought.

Young learners have efficiency with pronunciation which is sometimes not possible in the older. 12 year olds seem to have the right capacity for intaking the most efficiently and imitation than younger learners.

9/10 y/o learn in the following ways:

respond to meaning even if they don’t understand the individual words

learn indirectly more often than directly - take info from all sides, learn everything around them rather than focusing on topics they’re being taught

understanding doesn’t only come from explanation, but also from what they see and hear, and have a chance to touch and interact with.

Abstract concepts like grammar rules are difficult to grasp

enthusiasm for learning and curiosity about the world around them.

have a need for individual attention and approval from teacher

keen to talk about themselves and respond well to learning which uses themselves and their own lives as main topics in the class

limited attention span unless activities are engaging, otherwise they’ll get bored and lose interest after 10 minutes

10/11 y/o like games, puzzles and songs, and 12/13 y/o prefer activities built around dialogue, QA activities, and matching exercises

Adult language learners have these characteristics:

Engage in abstract thought: don’t have to rely on activities like games and songs - but may be appropriate for some students

Range of life experience to draw on

Have expectations about learning process and have their own set patterns of learning

Tend to be more disciplined than other age groups and are prepared to struggle with boredom

Have a rich range of experience which allows wide range of activities with them

Often have a clear understanding of why they’re learning and what they want to get from it.

Adults have a way of holding onto motivation which teens struggle with.

Adult characteristics which can make learning and teaching difficult:

Can be critical of teaching methods due to previous learning experiences predisposing them to one methodological style and makes them uncomfortable with unfamiliar teaching patterns. They may be hostile to certain teaching and learning activities which replicate the teaching received in earlier education

Experienced failure or criticism at school which makes them anxious and under-confident about learning a language

Older adults worry of intellectual powers being diminished with age. How much learning had been happening during adult life before they come to a new learning experience may also be related.

May stick to certain activities longer than younger learners. Indirect learning like reading, listening, and communicative speaking and writing, and learning consciously when appropriate. Encouraged to use life experience in the learning process.

Offer activities which are achievable by paying attention to the level of challenge presented by exercise. Listen to the students concert and modify what we do to suit their tastes in learning.

Some students are better at learning language than others, due to having a particular retention for things they hear and unusual memory

GOOD LANGUAGE LEARNER CHARACTERISTICS:

Tolerance of ambiguity

Positive task orientation - prepared to approach tasks in a positive manner

Ego involvement - success is important for student’s self-image

High aspirations, goal orientation, and perseverance

Students who can find their own way without always having to be guided through learning tasks, are creative, make intelligent guesses, and make opportunities for practice, and make errors work for them not against them, as well as using contextual clues

Willing to make mistakes

Encourage reading texts for general understanding without stopping to look up all the words they don’t understand: ask students to speak communicatively even when they have difficulty due to words they don’t know or can’t pronounce, and involve creative writing

A good language learner:

is a willing and accurate guesser

tries to get a message across even if specific

language knowledge is lacking

is willing to make mistakes

constantly looks for patterns in the language

practises as often as possible

analyses his or her own speech and the speech of others

attends to whether his or her performance meets the standards he or she has learned

enjoys grammar exercises

begins learning in childhood i has an above-average IQ

has good academic skills

has a good self-image and lots of confidence

Types of learners: Enthusiast - looks to the teacher for point of reference and concerned with the goals of the learning group

Oracular - also focuses on teacher but is more oriented towards the satisfaction of personal goals.

Participator - tends to group goals and group solidarity

Rebel - refers to learning group for their own point of reference is mainly concerned with the satisfaction of their own goals

Other categories:

Convergers: students by nature solitary, prefer to avoid groups, independent and confident of their own abilities, analytic and can impose their own structures on learning, tend to be cool and pragmatic

Conformists: students who prefer to emphasize learning about language over learning to use it. Tend to be dependent on those in authority and are perfectly happy to work in non-communicative classrooms doing what they’re told. This setting of students prefer well-organized teachers

Concrete Learners: though like conformists, they also enjoy the social aspects of learning and like to learn from direct experience. Interested in language use and communication rather than language as a system. Enjoy games and group work in class.

Communicative learners: language-use oriented, they’re comfortable out of class and show a degree of confidence and willingness to take risks. More interested in social interaction with other speakers of the language than they are with analysis of how the language works, and happy to work without guidance of teacher

Three position thinking - to get teachers and students to see things from other people’s points of view so they can be more effective communicators and interactions.

MI theory: Multiple Intelligences - People possess a range of intelligences rather than a single one: Musical/rhythmical, Verbal/linguistic, Visual/spatial, Bodily/kinaesthetic, Logic/mathematical, Naturalistic - recognizing and classifying patterns in nature, Emotional - ability to empathize, control impulse and self motivate, Intrapersonal and Interpersonal, each person has all of these but may have strengths in one or more being pronounced, these also influencing the same learning task may not be appropriate for all students.

MAY WANT TO GIVE QUESTIONNAIRE: When answering comprehension questions about reading passages I prefer to work: A. On my own. B. With another student. C. With a group of students

Work with students choice of learning styles if resistant to trying different styles.

Motivation - extrinsic/intrinsic - motivation from outside/inside - outside reasons for motivation could be benefits of travel and financial reward vs. inside individual could be a enjoyment of learning and desire to feel better about themselves. If student comes to love learning process, their extrinsic motivation is more reinforced to succeed.

FIND OUT WHAT OR WHO IS AFFECTING OR INFLUENCING THE STUDENTS MOTIVATION FOR LEARNING ENGLISH SINCE THEY FORM PART OF THE ENVIRONMENT FROM WHICH STUDENT ENGAGES WITH THE LEARNING PROCESS

Teaching based off of the student merely wishing to learn English to speak conversations or learn to read English websites should influence how you teach.

Motivation is necessary for students to succeed and so must be directed into new channels to become increased after initial motivation by curiosity when it’s new or create motivation where there is none.

Extrinsic motivation - Affect: involves students feelings and as teachers has a dramatic effect. Making known as a teacher, you care about the students progress regardless of participation and knowing their names.

Achievement: success is a great motivator like failure is a demotivator. The longer a student is made to feel motivated will give them continued success and stay motivated to learn. Making tests where they’re not too difficult or easy, involves student in learning tasks they can succeed in, and guiding them toward success by showing how to get things right next time.

Attitude: Students must believe we know what we’re doing, this confidence starting as the teacher walks in for the 1st time and the students perception of our attitude to our job. The way we dress, where we stand, the way we talk to the class, and we know the subject we’re teaching. The student must feel we’re prepared to teach English and this lesson in particular. One reason a class becomes undisciplined is if the teacher doesn’t have enough for the students to do or not sure what to do next. When students have confidence in the teacher, they’re more likely to remain engaged with what’s going on. If they lose confidence, it’s more difficult for them to keep motivation they’ve started with.

Activities: Students will have better motivation for things they enjoy. Teacher’s choice of what we ask them has importance on continuing engagement with learning process. Game-like communication and interactive tasks seem to be popular, but different students have different styles and preferences. Some may want to sing songs and write poems, whilst others are motivated by concentrated language study and reading texts. Matching lessons to students is what teachers must try to do, and the way to do it is keeping a constant eye on what they respond well to and what’s less engaging for them. Then the activities chosen will have a chance of helping keep students engaged with learning process.

Agency: Instead of always correcting the student, giving them the decision on what words they found difficult to pronounce may be more comfortable for them rather than assuming they all have the same difficulties. Wherever possible, students should be given the opportunity to make decisions. Allowing students to choose homework assignments they wanted and needed motivated the students to do the tasks set. Students taking responsibility for their learning is when agency occurs. Giving empowerment through agency is likely to keep their motivation over a long period.

CH6

Humanist sentiments have a teacher not standing in the front of the class to command the room, but moving about the class and helping the students where needed.

Foster good relationships with the groups in front of us so they work cooperatively in the spirit of friendliness and harmonious creativity.

A group conscious teaching style involves increasing encouragement and reliance of group’s own resources and active facilitating of learning autonomously in whichever maturity level of the group.

Students require leadership and direction which gives them clear focus and allows them to feel secure.

As group identity develops, teachers will relax and foster more democratic class practices for students to be involved in the process of decision-making and direction-finding.

This way of teaching is culturally biased and some teachers may find this style of teaching more difficult.

Roles of a Teacher: Controller - Teachers who are in charge of the class and the activity taking place often being lead from the front. Controllers take the register, tell the students things, organize drills, read around in various ways to exemplify the qualities of a teacher-fronted class. When giving explanations, organizing QAs work, lectures, making announcements or bringing class to order.

Prompter: In role-play activity, students lose thread of what is happening, or they’re lost for words (they have the thread but unable to continue productively due to lack of vocab). If the teacher decides to coax them on discreetly and supportively rather than allowing the student to work it out for themselves, this would be the prompting role. Make sure to prompt sensitively and encouragingly and with discretion, if too forward, it could take the student’s initiative away, but if too retiring, may not supply enough encouragement.

Participant: When teacher stands back from the activity and allows learners to get on with it and intervening after only to give feedback and/or correct mistakes. If a teacher decides to take part in activity, it’s to liven things up from the inside rather than prompting or organizing outside the group. It takes a certain skill to not be perceived as the authority and participate this way.

Resource: When students have questions about an activity is when teachers become a useful resource, as opposed to being a part of an activity or as a student is writing an essay and finding the teacher attempting to give resourceful advice may not be so welcome. If a teacher doesn’t have a ready answer for a student’s question, informing them of online resources or where the student can research further may be of use. Encouraging independent learning should always be an option to be given so the student doesn’t become over reliant on the teacher.

Tutor: Students who work on longer projects like process writing or preparing for a talk or debate can work with individuals or small groups, pointing them in directions they haven’t thought of yet of taking. In this way teachers combine the roles of prompter and resource and act as tutor, which is difficult in a large group. The most help will come from making sure to help each individual team or groups so no one feels left out and not to stay too long as to seem domineering.

Organizing students for certain activities involves giving students info, telling them how they’re going to do the activity, putting them in pairs or groups and closing things when it’s time to stop.

To begin we must get the students involved, engaged, and ready. Which means making sure it’s clear something new is about to happen and the activity will be interesting enjoyable and beneficial.

This is when the teacher says something like, Now we’re going to do this because, then offering the rational reason for the activity the students will perform.

This way, it’s not about doing it because the teacher says, they’ve prepared and hopefully will enthusiastically do the activity for the purpose they understand.

When the students are read, instructions will be shared, saying what the students will do first, then the next task, etc.

It’s important to get the level of language right to present instructions in a logical order and not confusing.

It’s a good idea to get students to give the instructions back in English or own language, as a check on whether they’ve understood.

An important tool for instruction is the teacher to organize and demo what is to happen. If students are using a chart or table ask other students questions and record their answers, like, getting a student up to the front to demo the activity with you may be worth any number of complex instructions.

Demonstration is always appropriate and will almost always ensure students have a better grasp of what they’re supposed to do that instruction can on their own.

Then it’s time for teachers to initiate the activity which is when the students will need to know how much time they have and when they should begin.

Finally, stop the activity when the students have finished or when other factors show they are to stop. Whether it’s due to boredom or some pairs or groups have finished before the others.Maybe the lesson is winding down and we want to give some summarizing comments. Now is time for organizing feedback whether it’s, Did you enjoy that? Or it’s a more detailed discussion which has taken place.

Teachers should think about content feedback - regarding roles of participant and tutor, as much as the use of language forms in form and use feedback- regarding our role as assessor.

With organizing feedback, we need to do what we say we are whether this has to do with prompt return of homework or our responses at the end of an oral activity. Students will judge us by the way we fulfill the criteria we offer them.

Summarizing the role of organizer: Engage -> instruct (demo) -> initiate-> organize feedback

Teachers will sometimes see themselves as actors, due to how they act in front of a class as opposed to daily life.

Since, if an activity requires energy, a teacher may act energetically because a game needs excitement and energetic behavior, encouraging, if students need a nudge to have a go, clearly, since we don’t want the game to fail through misunderstanding, and fairly, since students care about this in a competition situation.

If instead, students are involved in role-play, we should perform clearly, since the students need to know the parameters of the role-play, encourage, since students may need prompting to get them started, but also retiringly since once the activity is going on, we don’t want to overwhelm the students’ performance, with support due to students may needing help at various points.

Ex: ACTIVITY How the teacher should perform Team game Energetic, encourage, clearly fairly Role-play Clearly, encouragingly, retiringly, supportively Teacher reading aloud Commandingly, dramatically, interestingly Whole-class listening Efficiently, clearly supportively

Rapport - establishing an appropriate relationship with students creates a good learning environment in the class.

Making sure the teacher-student rapport is positive and useful; A class with a positive, enjoyable, respectful relationship between teacher and students and between the students themselves.

Part of this successful rapport has to do with the students perceiving the teacher as a good leader and a successful professional.

If teacher is well-organized and prepared, thinking about what they are going to do in the lesson, the students are likely to have confidence in the teacher, which is essential in the successful relationship between students and teachers.

This also extends to the teacher’s demonstrable knowledge of the subject they’re teaching and to their familiarity with the class materials and equipment.

This all shows the students they’re in good hands. Rapport also relies on how we interact with the students, despite being prepared and knowledgable teachers, if the interaction isn’t working, our ability to help the students were be severely compromised.

Successful interaction relies on 4 characteristics:

Recognizing students: knowing who the students are, their names, and understanding their characters. Putting names on cards or on jackets. Teacher can draw up a seating plan and have students sit in the same place for the 1st couple weeks. Noting whether a student wears glasses, are tall, etc. Due to wanting good rapport, memorizing names should be done.

Listening to students: Students respond to teachers who listen to them. Being present even outside of a lesson will be important and to show interest in what they have to say, since this could demotivate them if a teacher is dismissive or uninterested in what they’re saying. Convincing students we are interested is a part of the job to nurture them and make every sign they have our attention. Also pay attention to their comments on how they think they are progressing, and which activities they’re responding good and badly to, since if we continue teaching the same thing day after day without knowing the students reactions could make keeping rapport more difficult and damages maintaining a successful class. Listening doesn’t mean solely with our ears, but approaching them, making eye contact and looking interested is a part of this.

Respecting students: correcting students is always delicate, if we’re too critical, we can demotivate them, if we are constantly praising them, we risk turning them into praise junkies who need approval all the time. Some students are happy to be corrected robustly, others need more support and positive reinforcement. In either case, students need to know we are treating them respectfully, and not using mockery or sarcasm to give them despair with their efforts. Respect when dealing with problem behavior is also needed, seeing the behavior and student in a positive light will show the student respect, and they’re not negative but use professionalism to solve the problem.

Being even-handed: Most teachers warm to some students more than others. Teachers react well to those who take part, are cheerful and cooperative, take responsibility for their own learning and does what is asked without complaint. Sometimes teachers are less enthusiastic with those who are less forthcoming, and find learner autonomy challenging. Teachers should ask the people who don’t put up their hands more due to cooperative, talkative ones should be more controlled by the teacher. Treating students the same way regardless of easy cooperation shows professionalism and maintains equal rapport.

Specific ways to have students hear and understand language:

Mime and gesture: back in time (gesture over the shoulder) or forward in time (gesture forward pointing), but students may not always catch this so use miming with care. For instance, if a teacher is struggling with names still, gesturing to a student with an upturned palm with inclusion, and gesturing with welcome is more appropriate rather than seeming aggressively pointing at someone.

Teachers can be a model of language since students also receive this from textbooks and reading materials, along with audio and video. Teachers do this by performing a dialogue or reading text aloud.

Another way is to draw two faces on a board and stand in front of each one when we speak their lines. Make sure teacher is being heard and animate the performance with enthusiasm as appropriate for the convo being modeled.

Also judge appropriate speed, making sure however slow we go, we speak a natural rhythm and maintain normal intonation patterns to preserve the nature of the convo as much as possible.

Using poems or story-telling can be useful to engage students of all ages, but not to use it overly frequent.

Being aware of student talking time over teacher talking time is also important. Also knowing if they are at the lower language level, most students may not be finding moments outside the classroom to understand English in their community, so being aware they’re using the class as a comprehensible rough tuned version is what the teacher is their to provide. Since even if they don’t understand all of the words we say, they’ll get what’s being said, and more language gains are obtained by the student, which is significant. So, understanding teacher talking quality TTQ is also important with TTT.

Comparing native to non native speaker teachers and how they’re viewed still with a bias toward native speaker despite knowing either can be effective with linguistic confidence, which native speakers usually have more often.

CH7

Different learning contexts

Teaching one-to-one - esp popular with business students, but also good for students without normal school schedules and rather have individual attention instead of be in a group.

One to one teaching may be more difficult due to what the student may expect rather than the work they must put in to learn. Otherwise it is helpful to taylor a class to a single student and easier to change tasks, as well as having more talking time.

Guidelines for one to one teaching:

Make a good impression.

Be well prepared, give multiple options for what activities may interest the student.

Be flexible - if student is bored or tired, offer two minute break and return to a previous task to something studied or move forward to change pace.

Adapt to the student - allowing students interest lead tasks and activities.

Listen and watch - keep watch on how students respond to activities, teachers should listen more than talk, ask what students need more or less of, and what they like, this will help amend plans for specific students.

Give explanations and guidelines - when first meeting students, it’s important to explain what will happen, how the student will contribute to the program they’re involved in, and to lay down guidelines on what to expect from the teacher and what the teacher expects from them. It’s important for students to know they can influence the sessions by saying what they want or need more or less of.

Don’t be afraid to say no - for 2 specific situations: if it’s a personality match with a student, if completely unsuccessful. Usually we can overcome this by extreme professionalism and maintaining distance between ourselves and student and allowing content of lessons to drive the matters forward successfully. When they just don’t work, the teacher must prepare to terminate the class, if they’re working for themselves, or expect the institution they work for will make alternative arrangements for themselves and the student. We need to be able to tell a student when their demands are excessive and won’t help them learn, and we can’t do everything they’re asking for. Most students understand this.

Large classes - it’s difficult for individual attention but good for interaction due to how many possible teachers could be in the class which also give no chance to be bored.

For successful large group teaching:

Be organized: the bigger the group the more organized you must be and know what we’re going to do before the lesson begins. It’s more difficult to change tack or respond to individual concerns in a group larger than 4 or 5.

Establish routines: helps daily management when we and students recognize certain processes for efficient learning like, collecting and setting homework, making sure everyone’s present, getting into pairs and groups, etc. This is helpful for time management so starting this when we first intro the class is important which can take time at the start but will save time later.

Use a different pace for different activities: small class and face to face is easier to change pace, and early on we can understand the strengths and weaknesses of individuals. This is more difficult in large groups and we need to be more careful how we organize different activities with them. If we have students say something in a large class, we need to give them time to respond before charging ahead. If we are doing drills, we may be able to work at a fast pace, but if we ask students to think about something we have to slow the pace down.

Maximize individual work: the more individual work given even in a large class, the more we can manage effects of working with a large group as a whole. Having students get used to graded readers as part of individual reading programme. Having students write individually, giving responses to what they read and hear. Encourage students to make use of school library or self access centre. We direct them to language learning sites, or get them to produce their own blogs.

Use students: can have students take different responsibilities in the class like appointing class monitors to collect homework or hand out worksheets. Take the register under our supervision or organize classmates into groups. We can ask some students to teach the others, having individuals be in charge of a group who prepare arguments for debate or who are going through a worksheet. It could mean having individual students explain some language to their group, and choosing student leaders must be done with care as we monitor their performance carefully. This must be per each student being comfortable performing the leader’s tasks. As far as possible, allow all students some responsibility some of the time. Even for those who are weak in certain tasks, have them hand out worksheets, etc as positive reinforcement of being able to contribute.

Use worksheets: Going through worksheets individually with the group if not too large can be extremely beneficial for the feedback stage.

Use pairwork and groupwork: large classes, pair work and group work are important since they maximize student participation. For this type of work, instructions must be esp. clear, agree how to stop activity, which many teachers will raise their hands until students notice them and gradually quiet down, and to provide good feedback.

Use chorus reaction: since it’s difficult to use a lot of individual repetition and controlled practice in a big group, it may be appropriate to use students in chorus. Divide the class in 2 halves, and each side then speak a part in a dialogue, ask or answer a question or repeat sentences and words. ESP. USEFUL AT LOWER LEVELS.

Take account of vision and acoustics: using audio track or film clip, as long as a large group will be able to hear depending on class size.

Use the size of the group to your advantage: the main advantage of big groups are how big they are, humor is more funny, drama more dramatic and a good class feeling is warmer and more enveloping than it is in small groups. We should accept this potential lecturing, acting and joking in such situations, which allow organizing activities where students can perform this way too.

Large groups are challenging to teach so the ways above will allow some kind of success.

Managing mixed ability - mixed levels of proficiency can worry many teachers and is a major preoccupation due to planning be more difficult. In private language schools or language institutions we try to manage it with placement tests for the students so they can match other people’s level. No matter what, language level will be mixed.

THE RESPONSE FOR THIS IS DIFFERENTIATION. A variety of learning options will have different abilities and interests offered for students like, giving students different tasks: different things to read or listen to, and we can respond to them differently, and group them according to different abilities. Sometimes we don’t want to differentiate individuals, like when presenting new language. Plus real differentiation is difficult to achieve, but it’s clearly desirable response to the needs of the individual even though they’re a part of a group.

Working with students at different levels can be navigated by providing different material to individual needs. Allow the students to make choices on the content material they’ll be working with: give a range of grammar or vocab exercises to choose from. Give them a choice on a book to read from by topic and level.

If we can’t choose differentiation content, we have them do different things in response to content they’re looking at or listening to.

Give students different tasks: Give same reading text to all students but make different terms of the tasks we ask them to do in response to text. Ex. Having Group A interpret info in text and reproduce it in graphic form. Group B answer a series of open-ended questions. Group C may need the most support so are offered a series of multiple-choice questions and to pick the correct response from two or more alternatives because this could be easier for them than interpreting all the info themselves.

Give students different roles: within tasks students can be given different roles. Ex. Students are role-playing, the student asking the questions will be the ones in need of more guidance than the others. Ex. If students are preparing for a debate, Group A will have a list of suggested arguments to prepare and Group B, which need less support are told to come up with their own arguments.

Reward early finishers: if all students are doing the same tasks with the same content and some finish early, we should offer students extension tasks to reward their efforts and challenge them further. These should be chosen carefully, since asking them to do regular work on top of more seems taxing.

Encourage different student responses: even giving same tasks to all students, accepting different responses should be expected and allowed. Flexible tasks make a virtue of the differences between students. In response to a reading text for instance, we can give all students a number of tasks but know not all of the students will complete all of them. When asked for students to respond creatively to a stimulus we allow for differences in response. Ex. Asking for students to complete a sentence; the completions depend on how language proficient they are to some extent. In a poetry activity we may have them describe someone as if they are a type of weather. Students responses can vary from simply like, You are sunshine, or complex, You are sunshine after the rain, or even higher level, You are the gentle breeze of a dreamy summer afternoon. These activities are more appropriate when dealing with classes of mixed ability.

Identify student strengths (linguistic or non-linguistic): Including tasks which don’t demand linguistic brilliance and instead allows students to show off other talents they have is one way to make a virtue of students abilities. Ex. Students who have artistic talent can lead a design of a poster or wall chart. Students with scientific intelligence can be asked to explain a scientific concept before everyone is asked to read a science-based text. Students who have knowledge in contemporary music can be asked to select pieces to be played during group-work. This includes everyone rather than leaving out those who are weaker linguistically than their colleagues.

Some occasions students will be taught in a big group, or sometimes we’ll split them into smaller groups according to different abilities. Regardless of this, we will treat different students differently whether in groups or individually.

Responding to students: Taylor response to whichever kind of student you are dealing with when they ask a question. More sensitive students we will want to correct with more care than their robust colleagues. Some students need to see things in order to respond to them, whilst others respond better to having things explained verbally. When students work in pairs or group-work, we monitor their progress and intervene depending on how they’re doing. Students experiencing difficulty may need us to help them clear up some problems, we may have to correct some language use, or help them organize info logically. With internet tasks, we may have to direct what link to use for some while others may go further and ask them how they might say something more effectively, or suggesting an extension to what they’re doing. This is what’s meant by differentiation, but always paying attention to not ignore or exclude particular groups.

Being inclusive: With mixed ability classes, some students may get left behind or become disengaged to what’s happening. This happens when teachers spend more time with higher level students in a class, the students who are less linguistically able may feel they’re being ignored and become demotivated. On the other side, if we dedicate more time to the ones struggling the higher level students may feel neglected or unchallenged which has them quickly lose interest and develop an attitude which makes them difficult to work with.

For a mixed ability teacher, one must draw all the students into the lesson, and set a task with the whole group by maybe asking initial questions to build up a situation, and the teacher will start by working at a level all the students are comfortable with. The teacher will ask questions all the students understand and relate to so that their interest is aroused and so they all understand the goal they’re aiming for. Once they’re all involved with the topic or task, the teacher can allow for differentiation in any of the ways discussed above. The teacher’s initial task is to include and engage everyone, since those who feel excluded will soon behave like they’re excluded.

Flexible groupings: grouping students may be a flexible business for many tasks. Sometimes it’s to have different groups do different tasks, like reading different texts, depending on difficult of the texts or put students at different levels in the same group because the weaker students can benefit working with students in higher linguistic level since we believe higher level students will gain insights about the language by having to explain it to their colleagues.

Realistic mixed-ability teaching - the most ideal setting is being able to work with individuals-as-individuals all the time, but this is difficult with large classes, so planning for significant differentiation is daunting than building differentiation into lessons for a group we see all day every day. Depending on class set up and how large it is will determine the different types of tasks which can be given. If the school is equipped with a self-access centre so students can work individually on a variety of materials, it makes it easier to build individual learning programs for the curriculum.

If students have their own computers they can complete tasks upon their level of ability. Sometimes we may want to reinforce the group’s identity so we have them learn the same thing for info they all need, but will have to do the best we can with the circumstances. LEARNER TRAINING AND ENCOURAGEMENT OF LEARNER AUTONOMY IS THE ULTIMATE ACHIEVEMENT OF DIFFERENTIATION. When students take responsibility for their own learning, they are acting autonomously and differentiation is achieved. This autonomy can also raise complex issues which will be covered in CH23.

English-only environment may be the best and only potion depending on if the medium of communication is English and provides more attempts so the learning process can take care of itself esp. when students have different 1st language backgrounds which makes this the most realistic option. Banning the L1 language is “unfortunate” for a # of reasons, and in the first place, our identity is shaped somewhat by the language we learn as children.

With bilingual children who may have a home language and a public language, which shapes their way of seeing and communicating their mother tongue. Using their L1 may help them translate what they’re doing in English in their heads, which is why it should be acknowledged as being a part of learning, both languages may be used in the class to further the learning of the 2nd.

Benefits to using L1 language in L2 class: It’s helpful for the student to use their L1 language during the process of learning so they can further absorb the L2 being learned and to compare the differences between languages.

Translation activities can be useful, whether straight translation of short texts and translation of a summary from a longer text may be helpful in group settings so they can discuss any issues which reveal themselves more in a group rather than thinking on one’s own.

Translation could be considered the 5th skill after reading writing speaking and listening. It’s desirable for students to use their L1 when talking about learning.

For lower level students it’s easier to get a needs analysis when they use their L1 rather than have them struggle through with English.

Comparison between the two languages will happen for the student naturally so it will help them understand certain types of errors by showing them the differences.

It’s also a way of reviewing how well students have understood grammar and lexis at the end of a unit of study.

Disadvantages of using the L1 in the L2 class: A teacher doesn’t always share the L1 or the L1 of all the students, but the student will compare languages consciously or subconsciously. Teacher’s have some way of asking, Can you translate it back into English? Do you have an expression for this in your language? — most useful when speaking of idioms or metaphor use. Overuse of L1 can restrict the use of English exposure.

How and when to use and allow use of students’ L1 in class:

Acknowledge the L: Discussing learning process and L1 and L2 issues with the class.

Use appropriate L1, L2 activities: can include translation exercises or specific contrasts between the 2 languages in areas of grammar, vocab, pronunciation or discourse. Discussing code of conduct or best ways of keeping vocab notebooks or giving announcements is best in the context of a largely English-use classroom.

Differentiate between levels: Using L1 for explanations and rapport-enhancement at lower levels, becomes less appropriate as students’ English improves. After which can use L1 and L2 for comparisons and encourage the fifth skill of translation.

Agree clear guidelines: Students should know when to use mother tongue is productive or not. For ex. It wouldn’t be useful during an oral communicative activity. Finding a good compromise for students on when to use L1 and when it is counter-productive must be agreed on.

Use encouragement and persuasion: When going around to students during speaking activities, use of phrases like, Why not try stop using L1 and use English? often works, especially after discussing when to use it. If encouragement doesn’t work, you can temporarily stop activity and explain to students since activity is designed to give them practice in speaking English, it makes little sense if they do it in another language. Sometimes it will change the atmosphere so they go back to the activity with new determination.

Ch8

Feedback on students’ work has more effect on achievement than any other single factor. Making sure the feedback given is appropriate for the student concerned and the activity they’re involved in will be important. Mistakes can be divided into 3 broad categories: slips - mistakes which students correct themselves once the mistake is pointed out, errors - mistakes which they can’t correct themselves and need explanation, and attempts - when a student tries to say something but doesn’t yet know the correct way of saying it. The most concern for teachers are the errors, though students Attempts will show a lot of their current knowledge and could provide chances for opportunistic teaching.

2 sources of errors which students display:

L1 interference: Where a student’s L1 and the variety of English they’re learning come into contact, there are often confusions which provoke errors in the learner’s use of English. This can be at the level of sounds: Arabic doesn’t have a phonemic distinction between f and v, and they may say ferry when they mean very. It can also be at the level of grammar, the L1 can have a subtly different system, like French students usually have trouble with present perfect because there is a similar form in French but at the same time concept is expressed slightly differently. Or Japanese students may have problems with article usage due to Japanese not using the same system of reference, etc. Lastly, it may at be at the level of word usage, when similar sounding words have slightly different meanings, like libreria in Spanish, means bookshop or embarasada means pregnant.

Developmental errors: in child language development, there’s a phenomenon called over-generalization. An ex., a child starts by saying, they went, they came, etc. Then starts saying they goed, they comed, which is the child over-generalizing. Later on, this is sorted out when the child gets more sophisticated understanding or goes back to saying went and came and also handling regular past tense endings. This also happens with second-language learners, this a natural process of language learning. When responding to errors, teachers should be seen providing feedback and helping the reshaping process rather than telling the students they’re wrong.

Assessing student performance can come from the teacher or from the students. When teachers assess students, it can be explicit, like, that was really good, or implicit, like during a language drill we pass on to the next student without making comment or correction, which can be a danger for the student thinking the silence means something else.

Students will receive teacher assessment in the form of praise or blame, so seeing our role as encouraging the students with praise for work well done, is vital for students motivation and progress.

So, this could be seen as “medals” and “missions”, the former given for doing something well, and the latter to direct them where to improve.

Try to give every student some reinforcement with every lesson and avoid only rewarding conspicuous success.

If we measure every student against what they’re capable of doing and not against the group as a whole, then we are in a position to give medals for small things, including participation in a task or evidence of thought or hard work, rather than reserving praise for big achievements alone.

Praise is usually responded to well by students, but over-complimenting them on work whilst their own self-eval tells them they haven’t done well may be counter productive. Over praise can create praise junkies and blinds them to true progress they make.

Assessment must be handled with subtlety, so combining appropriate praise with helpful suggestions on how to improve will have much greater chance of contributing to student improvement.

Focusing on incorrect verb tenses, pronunciation or spelling will be easy to advise but include what they’re saying and writing. Language production activities require the last 2.

Asking students to give opinions and write creatively or setting up a role-play or having students put together a school newspaper or writing a report, all need feedback on what students say rather than on only how they say it.

Excluding exams, there are many ways to assess student work:

Comments - saying good or nodding in approval showing clear signs of positive assessment. When negative, we may indicate something has gone wrong or saying things like, this isn’t quite right, but also acknowledge the students’ efforts first before showing something’s wrong, and then suggest future action (a mission).

Same applies for written work, but it will depend on what stage students’ writing is at. Our responses to finished pieces of written work will be different from the help students receive as they work with written drafts.

Marks and grades - Students getting good grades affects motivation in a positive way, provided the level of challenge for the task is appropriate. Bad grades can be disappointing, so deciding on what basis to do this and how to describe to the students will be necessary.

Giving a grade for a homework exercise or a test depending on multiple choice, sentence fill-ins or controlled exercise types will be fairly easy for students to understand and why they achieve the marks or grades given to them.

It’s more difficult for creative activities where students produce spoken or written language to perform a task. Awarding of grades in this case must be a bit more subjective which despite this, students may have enough confidence in you as a teacher to accept our judgement, esp where it coincides with their own assessment of their work.

Where this isn’t the case or where they compare their mark with other students and not agree with what they find, it will be helpful for us to demo clear criteria for the grades given either offering a marking scale or written or spoken explanation of the basis for the judgement.

Grading structure varies by culture, so providing a grading scale will be necessary if you want the student to understand how it works, so many teachers prefer feedback and comments, this way clear responses are given to the students without risking a grading system confusion which demotivates them unnecessarily.

Giving marks and grades should be reserved for verbal activities, homework or end of period time, before weekend or semester.

Reports - end of term or year, teachers write reports on their students’ performance, it showing how well the student has done in the recent past and reasonable assessment of future prospects.

This also requires a balance between positive and negative feedback. Like all feedback, students have a right to know strengths as well as weaknesses, this can lead to further improvement and progress, and it’s greatly increased if taken together with student’s own assessment of their performance.

Teachers can help students self assessment by helping them develop awareness of how effective they are at monitoring and judging their own language production, which will greatly enhance learning.

Student self assessment is bound in with learner autonomy since if we can encourage them to reflect upon their own learning through learner training or on their own away from the class, we are equipping them with a powerful tool for future development.

Involving students in assessment of themselves and peers occurs when we ask the class, Do you think that’s right?, After writing something we heard someone say up on the board, or asking the class the same question when one of their number gives a response.

At the end of an activity we can also ask how well they think they have got on, or tell them to add a written comment to a piece of written work they have completed, giving their own assessment of that work. We may ask them to give themselves marks or a grade and then see how this tallies with our own.

Ex. At the end of a course book unit, we can ask students to check what they can now do, like, now they know how to get their meaning across in a convo/ use past passive/interrupt politely in a convo, etc.

This type of self eval is the heart of “can do”, students able to measure themselves by saying what they can do in various skill areas.

ALTE statement for six levels A1-C2 can be found www.alte.org/can_do/general.php

Feedback for verbal work, shouldn’t necessarily deal with oral production in the same way. Deciding how to react to performance will depend on the stage of the lesson, activity, and type of mistake made, as well as the student making the mistake.

Accuracy and fluency - when a particular activity in the class is designed for students’ complete accuracy, like study of a piece of grammar, pronunciation exercise or vocab work, or whether teachers are asking students to use the language as fluently as possible. We need to be clear on the difference between “non-communicative” and “communicative” activities, since the former ensures correctness, and latter designed to improve language fluency.

Teacher intervention, when an activity is stopped in order to correct a specific error, is sometimes preferred by the student.

During communicative activities, it is generally understood a teacher shouldn’t interrupt students mid-flow to point out grammatical, lexical, or pronunciation errors, since to do so interrupts the communication and drags an activity back to the study of language form or precise meaning.

Traditionally, speaking activities in class, esp activities at the extreme communicative end were though to act as a switch to help learners transfer learnt language to the acquired store or a trigger, forcing students to think carefully about how best to express the meanings they want to convey.

This remains the heart of the focus on forms view of language learning. Part of the value of these activities lies in the various attempts students must make to get their meaning across.

Processing language for communication is the best way of processing for language acquisition.

Teacher intervention could raise stress and stop acquisition completely in these circumstances.