Learning Teaching -The Essential Guide to English Language Teaching (CELTA course study material #2) By Jim Scrivener

These are my notes and are pretty much an edit of the original text and was a bit more difficult due to being in the first person, which I negotiate by using Scrivener’s last name or ‘teacher’.

CH1 Starting out

This CH offers general intro to ways of working in a language class and to a range of teacher and learner roles. It also addresses some important questions about how people learn.

Classrooms at work - Task 1.1 Class snapshots - A friend who knows nothing about language teaching asks you to describe a snapshot of a typical moment in a language class, a picture capturing the look, atmosphere, the learners’ mood, the teacher’s attitude, etc. What would your instant snapshot show?

Commentary - Your image probably captures some assumptions you hold, about what a teacher’s job is, what learners can do and how they should work, etc.

If you’re on a training course and haven’t started yet, your snapshot may be different from a teacher who’s been working 20 years.

In this book we’ll look in detail at lots of lesson ideas, activities, methods and techniques, but before we do this, it may be useful to get a more general pic of what goes on in language teaching, to look round a few class doors and glimpse what’s going on.

Watching different classes - one of the most useful things is simply watching other people teach. Scrivener often takes away tangible things from this observation, such as ideas for specific activities, the pace they work at or a particular something the teacher said or did.

Some aspects of lessons can be difficult to interpret. Much of the magic which makes a good lesson often attributed purely to natural skill or personality is something which is almost always achieved by very specific actions, comments and attitudes, even when the teacher isn’t aware of what they’re doing, and due to this, we can study these things and learn from them.

Task 1.2 Different lessons - Read the following brief snapshot descriptions form different lessons in different locations.

Which one, if any is most like how you see yourself as a teacher? Are there any characteristics or approaches you find interesting and would like to use yourself or would reject?

Classroom 1: Andrea

Andrea’s working with 34 14-yr-old learners. Although the large desks are fixed in their places, she’s asked the students to move so they’re sitting around both sides in ways they can work in groups of six or seven.

Each group has finished discussing and designing a youth club on a sheet of paper and is now working on agreeing a list of ten good arguments to persuade the other groups to choose its youth club design rather than one of the others.

Each group will have to make a presentation of its arguments in front of the class in about ten minutes’ time. There’s a lot of noise in the class and Andrea’s walking around listening in unobtrusively to what is going on in the groups.

She smiles when hearing good ideas, but she isn’t intervening or taking any active part in the convos. She answers basic questions when a learner asks, if someone wants to know the word for something, but she avoids getting involved in working closely with a group, even with one group which’s getting stuck, in this case, she makes a quick suggestion for moving forward and then walks away to another group.

Class 2: Maia

At a first glance, nothing much seems to be happening here, and Maia’s sitting down in a circle with her 8 students, and they’re chatting, fairly naturally, about some events from the previous day’s news.

Although Maia isn’t doing much overt correction, after watching the lesson for a while it’s possible to notice she’s doing some very discreet teaching, she’s managing the convo a little, bringing in quieter students by asking what they think and helping all learners to speak by encouraging, asking helpful questions, echoing what they’ve said, repeating one or two hard-to-understand sentences in corrected English, etc.

Class 3: Lee

Lee’s standing at the front of a class of eleven young adult students. He’s intro-ing going to as a way of talking about predicted events in the future.

He’s put up a large wall chart pic on the board showing a policeman watching a number of things in the town centre.

The pic seems to immediately suggest a number of going to sentences such as They’re going to rob the bank, He isn’t going to stop and It’s going to fall down.

Lee’s pointing at parts of the pic and encouraging learners to risk trying to say a going to sentence. When they do, he gently corrects them and gets them to say it again better.

Sometimes he gets the whole class to repeat an interesting sentence. It’s interesting he’s actually saying very little himself; most of his interventions are nods, gestures, facial expressions and one- or two-word instructions or short corrections.

Generally, the learners are talking rather more than the teacher.

Class 4: Paoli

Paoli’s lesson is teaching some new vocab to an adult evening class of older learners; the current lesson stage is focused on learner practice of the new items. Everyone in class is sitting in a pair, face to face.

They’re using a handout designed by Paoli which gives the learners in each pair, known as A and B, slightly different info.

The task requires them to use some of the new vocab in relatively natural ways to try and discover info from their partner.

There’s a lot of talking in the room, though it’s clear not everyone’s participating to an equal degree. One or two pairs are almost silent, and one pair seems to be whispering in their own language rather than in English.

Paoli’s moving round the room trying to notice any such problems and encouraging students to complete the task in the intended way.

Commentary - We’ve glimpsed four different lessons. The descriptions below summarize some distinctive features of each.

Some typical language-teaching classes - the first class, Andrea, described above involved groups working cooperatively on a task.

The teacher saw her role as primarily managerial, making sure the activity’s set up properly and being done properly.

She took care she allowed enough space, time to think and plan without interference or unhelpful help, so learners could get on and achieve the result.

In the second class, Maia, we saw a teacher apparently doing fairly little which may be traditionally viewed as teaching.

However, even at this glimpse, we’ve noticed something’s going on and the teacher was managing the convo and the language more than may have been apparent at first glance. Is this a valid lesson?

We’ll look at possible aims for lessons like the 1st and 2nd snapshots in CH9.

The 3rd class, Lee involves a lesson type known as a presentation, the teacher’s drawing everyone’s attention to his focus on language.

Interestingly, although the teacher’s intro-ing new language, he’s doing this without a great deal of over explanation or a high quantity of teacher talk. We look at grammar presentations in CH7.

In the 4th lesson, the learners are doing a pairwork vocab task. The teacher’s role’s initially to set up the activity, and at the end it will be to manage feedback and checking.

At the moment, he can relax a little more, as nothing much requires to be done beyond monitoring if it’s being done correctly.

Out of these four lessons, we’ve seen relatively little overt teaching in the traditional manner, although we’ve seen a number of instances of the teacher managing the seating and groupings, managing the activities, starting, monitoring, closing them, managing the learners and their participation levels, and managing the flow of the conversation and work.

It’s reasonable to argue much of modern language teaching involves this class management as much or more than it involves upfront explanation and testing many people imagine as the core of a teacher’s job.

This is partly to do with the peculiar subj matter we work with, the language we’re using to teach with is also the thing we’re teaching.

Although there’s a body of content in language teaching, the main thing we want our students to do is use the language themselves, and therefore there’re many reasons why we mainly want our students to do more and therefore for us to do and talk less.

What is a teacher? - language learners don’t always need teachers, since they can set about learning in a variety of ways.

Some DIY, or pick up the language by living and communicating in a place where the language is used, known as immersion.

Of course, many student learn in classes with other students and a teacher, and much language learning will involve elements of all three ways: self-study, picking it up, and class work.

Task 1.3 Remembering teachers you’ve known - 1 think back to some teachers of any subj you’ve had in your life. What do you remember about them and their lessons? The teacher’s manner? How you felt in their presence? Can you recall any specific lessons? Specific teaching techniques? What it’s like to be a student in the room? What words or phrases characterize the atmosphere of the classes, eg. Positive, encouraging, boring, friendly, like an interrogation, sarcastic, humorous, respectful, scary, quiet?

2 To what extend do you think your personal style as a teacher’s based to some degree on these role models?

Commentary - ‘Entertainer’ teaching - learners come to class to learn a language rather than to be amused by a great show.

Certainly no one would wish their lessons to be boring, but it’s important to check out if the classes of an entertainer style of teacher are genuinely leading to any real learning.

It’s easy to get swept up in the sheer panache of one’s own performance; the teacher who constantly talks a lot, tells stories and jokes, amuses the class with their antics, etc can provide a diverting hour, but it may simply cover up the fact very little has been taken in and used by the students.

The monologue may provide useful exposures to one way of using language, but this isn’t sufficient to justify regular lessons of this kind.

Many teachers suspect this performer style is a goal they should aim for, partly due to an influence form films about teaching, but there’s a fine line between creating a good atmosphere and good rapport in class and becoming an entertainer. Rapport is crucial but entertainment is much less so.

Task 1.4 Traditional teaching - despite varying from country and cultures, there’s still many aspects of traditional teaching which’er familiar to many.

List some of these characteristic features of traditional teaching, Where does the teacher stand/sit? How are students seated? How is the class managed? What do you think are the disadvantages of a traditional teaching approach for language teaching and learning?

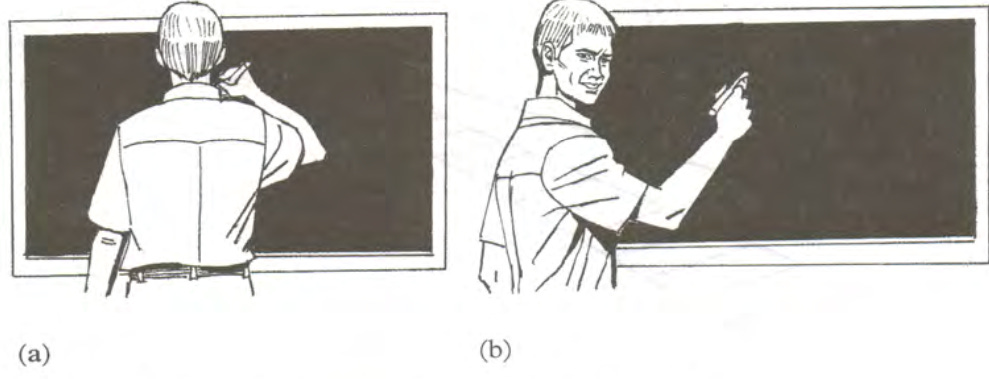

Commentary - Traditional teaching comes in many varieties, but is often characterized by the teacher spending quite a lot of class time using the board to explain things, as if transmitting knowledge to the class, with occasional questions to or from the learners.

After these explanations, the students will often do some practice exercises to test whether they’ve understood what they’ve been told.

Throughout the lesson, the teacher keeps control of the subj matter, makes decision about what work is needed and orchestrates what the students do.

In this class, the teacher probably does most of the talking and is by far the most active person. The students’ role is primarily to listen and concentrate and, take notes perhaps, with a view to taking in the info.

Often the teacher takes as if by right, permission to direct, give orders, tell off, rebuke, criticize, etc, possibly with limited or no consultation.

This transmission view of the role of a teacher’s relatively widespread, and in many cultures represents the predominant mode of education.

Students will expect a teacher’ll in this way, and fellow teachers may be critical or suspicious of teachers who don’t.

In such cases, it’s important to remember your choice oof methodology isn’t simply a matter of what you believe to be best, imposed at any cost, but it’s also about what’s appropriate in a particular place with particular people.

What you do in any school or with any learner will often represent your best compromise between what you believe and what seems right in the local context.

You then have the interesting possibility of starting to persuade your colleagues and students to your ideas… or may learning from them about why their approaches work better.

The process by which traditional teaching’s imagined as working is sometimes characterized as jug and mug, the knowledge being poured from one receptacle into an empty one.

It’s often based on an assumption the teacher’s the knower and has the task of passing over knowledge to the students, and having something explained or demo-ed to you will lead to learning, and if it doesn’t, it’s due to the teacher having done this job badly or the student is lazy or incompetent.

In many circumstances, lecture or explanation by a teacher may be an efficient method of informing a large number of people about a topic.

However, if our own educational experience has mainly been of this approach, then it’s worth pausing for minute and questioning whether this is indeed the most effective or efficient teaching method.

Whereas most teachers will need to be good explainers at various points in their lessons, a teaching approach based solely or mainly on this technique can be problematic.

The importance of rapport - What creates the distinctive atmosphere of each teacher’s class? What makes the difference between a room where people are defensive and anxious, and a room where people feel able to be honest and take risks?

Teachers and trainers often comment on the importance of rapport between teachers and students. The problem is, whereas rapport is clearly important it’s also notoriously difficult to define.

Sometimes people equate it with being generally friendly to your students. While this is a reasonable starting point, a wider definition is needed, involving many more aspects to do with the quality of how teacher and learners relate.

This does raise a problem though, if a significant part of a class’s success is down to how well the teacher and students relate, does this suggest successful teachers are born, and if they don’t naturally relate well to people, then they’re a write-off?

Is your rapport 100% natural or is it something which can be worked on and improved.

Task 1.5 Creating a positive learning atmosphere - Fig 1.1 lists some features which may be important in creating a positive relationship and a positive learning atmosphere. Decide which items are inborn and which could be worked on and improved.

In a positive learning atmosphere the teacher…

(In cloud bubbles)

really listens to his/her students

shows respect

has a good sense of humor

inspires confidence

is honest

is patient

(More listed)

Fig.1.1

Commentary - Arguable, but all of the above are things which can be studied and improved on. Some ar more difficult than others. Of course, although a good start, a positive learning atmosphere isn’t everything.

Being jokey, chatty, and easygoing doesn’t necessarily lead to good teaching, one teacher happened to be very friendly and funny, but his lessons ended in confusion.

Contrastingly, lessons from one of the quieter, more serious teachers were often memorable. This is simply the first building block of teaching, but it’s important.

Respect, empathy and authenticity - 3 core teacher characteristics which help to create an effective learning environment are respect, a positive and nonjudgmental regard for another person, empathy, being able to see things form the other person’s perspective, as if looking through their eyes, and authenticity, being oneself without hiding behind job titles, roles or masks.

When a teacher has these qualities, the relationships within the class are likely to be stronger and deeper, and communication between people much more open and honest.

The educational climate becomes positive, forward-looking and supportive. The learners are able to work with less fear of taking risks or facing challenges.

In doing this, they increase their own self-esteem and self-understanding, gradually taking more and more of the responsibility for their own learning themselves rather than assuming it’s someone else’s job.

Out of the 3 teacher characteristics, authenticity is most important, to be yourself, not to play the role of a teacher, but to take the risk of being vulnerable and human and honest.

The foundation of rapport is to learn yourself enough you know what style you have and when you’re being truthful to yourself.

Although there are some practical techniques to improve communication with others, real rapport’s something more substantial than a technique which can be mimicked.

It’s not something you’d do to other people. It’s your moment by moment relationship with other humans. Similarly, respect or empathy or authenticity aren’t clothes put on being walking into the class, or temporary characteristics you take on for the duration of a lesson.

You can’t role play respect or any other qualities, it’s rooted at genuine intentions. In order to improve the quality of our relationships in class, we don’t need to learn new techniques, we need to look closely at what we’re waning for our students, how we really feel about them.

It’s our attitude and intentions rather than our methodology we may need to work on. This book can’t teach how to do this, so the main subject matter of the book concerns the more technical aspects of creating a successful class.

Three kinds of teacher - There’re obviously many ways of teaching, and part of the enjoyment of being a student in a good class is in sharing unique personality identity, style, skills, and techniques a teacher brings to a lesson. Having said that, it sometimes gives things a clearer perspective if we simplify. There may be three broad categories of teaching styles, summarized in Fig. 1.2.

The explainer - Many teachers know their subj matter very well, but have limited knowledge of teaching methodology.

This kind of teacher relies mainly on explaining or lecturing as a way of conveying info to the students. Done with style or enthusiasm or wit or imagination, this teacher’s lessons can be very entertaining, interesting and informative.

The students are listening, perhaps occasionally answering questions and perhaps making notes, but are mostly not being personally involved or challenged.

The learners often get practice by doing individual exercises after one phase of the lecture has finished.

The involver - This teacher also knows the subj matter which’s being dealt with. In our case, this is essentially the English language and how it works, however, she’s also familiar with teaching methodology; she’s able to use appropriate teaching and organizational procedures and techniques to help her students learn about the subj matter.

Teacher explanations may be one of these techniques, but in her case, it’s only one option among many she has at her disposal.

This teacher’s trying to involve the students actively and puts a great deal of effort into finding appropriate and interesting activities which’ll do this, while still retaining clear control over the class and what happens in it.

The enabler - the third kind of teacher is confident enough to share control with the learners, or perhaps to hand it over to them entirely. Decision made in her class may often be shared or negotiated.

In many cases, she takes her lead from the students, seeing herself as someone whose job is to create the conditions which enable the students to learn for themselves.

Sometimes this’ll involve her in less traditional teaching; she may become a guide or counsellor or a resource of info when needed.

Sometimes, when the class is working well under its own steam, when a lot of autonomous learning is going on, she may be hardly visible.

The teacher knows about the subj matter and about methodology, but also has an awareness of how individuals and groups are thinking and feeling within her class.

She actively responds to this in her planning and methods and in building effective working relationships and a good class atmosphere. Her own personality and attitudes are an active encouragement to this learning.

Subj matter Methodology People

Explainer ✓

Involver ✓ ✓

Enabler ✓ ✓ ✓

Fig. 1.2 Three kinds of teacher

These 3 descriptions of teachers, are of course very broadly painted, and there’s no way to categorize all teaching under 3 headings; meany teachers will find elements of each category are true for them, or they move between categories depending on day, the class, and the aims of a lesson.

However, this simple categorization may help you to reflect on what kind of teaching you’ve mostly experienced in your life so far and may also help you to clarify what kind of teacher you see yourself as being now or in the future.

On teacher-training courses, participants initial internal image of a teacher’s based on the explainer, but who’re keen to move to becoming an involver in their own teaching.

Such a move may be your aim in reading this book, and the book’s mainly geared towards giving you info, ideas, options and starting points which may help you reach this goal.

Essentially this is a book of methodology. Throughout the book Scrivener keeps in mind the important skills, qualities, values and techniques associated with the enabling teacher and to give guidance and info which may influence your role and relationships in the class.

When Scrivener thinks back on his experiences of being taught, it’s the teaching techniques I remember least.

The teacher he remembered most was the one who listened, encouraged, and respected his views and decisions.

Curiously, this teacher did the least teaching of the subj matter and was technique free, being himself in class. Scrivener was able to focus on his learning rather than the teacher’s teaching.

Task 1.6 Explainer, involver, enabler - think of some people you have been taught by in the past. Which of the three descriptions above best suits each one? This may give some idea about which images of teaching you’ve been exposed to and influenced by.

Teaching and learning - Let’s look outside the class for a moment. How do people learn things in everyday life? By trial and error? By reading a manual and following the instructions? By sitting next to someone who can tell you what to do and give feedback on whether you’re doing OK?

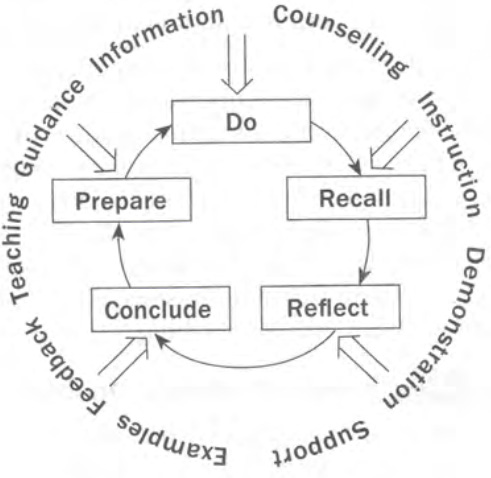

An experiential learning cycle - The process of learning often involves five steps, see fig. 1.3:

1 doing something;

2 recalling what happened;

3 reflecting on that;

4 drawing conclusions from the reflection;

5 using those conclusions to inform and prepare for future practical experience.

(In a circle)

Do→Recall→Reflect→Conclude→Prepare→back to Do

Fig. 1.3 an experiential learning cycle

Again, it’s important to distinguish between learning and teaching. Info, feedback, guidance and support from other people may come in at any of the five steps of the cycle as seen below Fig. 1.4, but the essential learning experience’s in doing the thing yourself.

Fig. 1.4 teaching and the experiential learning cycle

This cycle suggests a number of conclusions for language teaching in the class. For ex:

If this cycle does represent how people learn, then the jug and mug explanation-based approach may be largely inappropriate if it dominates class time. Giving people opportunities to do things themselves may be much more important.

If worrying less about teaching techniques and trying to make the enabling of learning the main concern, ie. The inner circle of the diagram rather than the outer one, one could become a better teacher.

Ensuring students get practical experience in doing things, eg. In using language rather than simply listening to lectures about language.

It may be being over-helpful as a teacher could get in the way of learning. The more the teacher does themselves, the less space there’ll be for the learners to do things.

It may be useful to help students become more aware about how they’re learning, to reflect on this and to explore what procedures, materials, techniques or approaches would help them learn more effectively.

It’s OK for students to make mistakes, to try things out and get things wrong and learn from it… and it’s true for the teacher as a learning teacher, as well.

One fundamental assumption behind this book and the teaching approaches suggested, is people learn more by doing things themselves rather than by being told about them.

This is true both for the students in your classes and for you, as you learn to be a better teacher. This suggests, for ex, it may be more useful for a learner to work with others and role play ordering a meal in a restaurant, with feedback and suggestions of useful language, than it’d be to listen to a fifteen-minute explanation from the teacher of how to do it correctly.

A second assumption is learners are intelligent, fully functioning humans, not simply receptacles for passed-on knowledge.

Learning isn’t simply a one-dimensional intellectual activity, but involves the whole person, as opposed to only their mental processes such as thinking, remembering, analyzing, etc.

We can no longer be content with the image of the student as a blank slate. Students may bring pen and paper to the lesson, but they also bring a whole range of other, less visible things to class: their needs, their wishes, their life experience, their home background, their memories, their worries, their day so far, their dreams, their anger, their toothache, their fears, their moods, etc.

Given the opportunities, they’ll be able to make important decisions for themselves, to take responsibility for their learning and to move forward, although their previous educational experience may initially predispose them to expecting you, the teacher, need to do all this for them.

New learning’s constructed over the foundations of our own earlier learning. We make use of whatever knowledge and experience we already have in order to help us learn and understand new things.

Thus the message taken away from any one lesson is quite different for different people. The new learning has been planted in quite different seed beds.

This is true both for your learners meeting a new tense in class and for you reading this paragraph and reviewing it in the light of your own previous experience and knowledge.

You can check this out for yourself. Is the info you’re finding in this book being written in your head on a sort of blank slate or is it connecting in some manner with your previous knowledge, ideas, thoughts, prejudices?

The two assumptions listed above inform Scrivener’s teaching. They remind him his performance as a teacher’s only one, possibly minor, factor in the learning might occur.

They remind him some of the teaching he does may actually prevent learning. They remind him teaching’s fundamentally about working with people and about remaining alive to the many different things which go on when people hack their own path through the jungle towards new learning.

Although this book concentrates mainly on teaching techniques, it’s important to bear in mind knowledge of subj matter and methodology are, on their own, insufficient.

A great deal of teaching can be done with those two, but he suspects the total learning wouldn’t be as great as it could be.

However, an aware and sensitive teacher who respects and listens to her students, and who concentrates on finding ways of enabling learning rather than on performing as a teacher, goes a long way to creating conditions in which a great deal of learning’s likely to take place.

Methodology and knowledge of subj matter are important, but may not necessarily be the most important things.

We never know how much learning is taking place. It’s tempting to imagine if teaching’s going on, then the learning must be happening; but in fact, teaching and learning need to be clearly distinguished.

Here’s the great and essential formula, one which all teacher should probably remind themselves of at least once a day!

T≠L

Teaching doesn’t equal learning. Teaching doesn’t necessarily lead to learning. The fact the first is happening doesn’t automatically mean the other must occur.

Learning, of anything, demands energy and attention from the learner. One person can’t learn anything for anyone else. It has to be done by your own personal effort.

Nobody else can transmit understanding or skills into your head. It’s quite possible for a teacher to be putting great effort into their teaching and for no learning to be taking place; similarly, a teacher could apparently be doing nothing, but the students be learning a great deal.

As we’ll find when talking to some students and parents, there’s a surprisingly widespread expectation which simply being in a class in the presence of a teacher and listening attentively is somehow enough to ensure learning will take place.

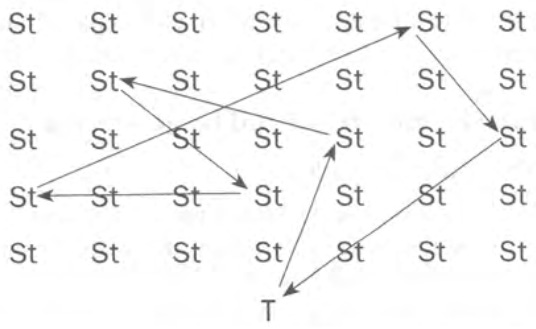

This suggests a very active role for the teacher, who’s somehow responsible for radiating knowledge to the class. Conversely, there’s an assumption of a more passive role for the student, whose job is mainly to absorb and store the received learning, but this isn’t an accurate view of how people learn. In a traditional class of say, 25 students, one less’s being taught, but we could equally think of it as a range of different lessons being received, as shown in Fig. 1.5:

(More ex’s given, 3 provided)

That’s really interesting.

Ah-some of that makes sense now.

I’m not involved at all.

Fig. 1.5 Different perceptions of the same lesson

Perhaps some students are listening and trying to follow the explanations, but only one of them is able to relate it to her own experiences; some other students are making detailed notes, but not really thinking about the subj; one person is listening and not really understanding anything; one, having missed the previous lesson, thinks the teacher’s talking about something completely different; three students are daydreaming; one is writing a letter; etc.

Here, the teaching’s only one factor in what’s learned. Indeed, teaching’s actually rather less important than one may suppose.

As a teacher, Scrivener can’t learn for his students, only they can do this, what he does is help create the conditions in which they may be able to learn.

This could be by responding to some of the student complaints above, perhaps by involving them, by enabling them to work at their own speed, by not giving long explanations, by encouraging them to participate, talk, interact, do things, etc.

How useful are explanations? - Language learning, esp, seems not to benefits much from long explanations.

If the explanation’s done in the language being learned, then there’s an immediate problem; learners have limited understanding of this new language, and therefore any lengthy or difficult explanation in the target language will be likely to be more difficult for them than the thing being explained, and even if the explanation’s done in their native tongue, explanations about how language works, while of some value, seem to be most useful in fairly brief hints, guidelines and corrections; language learners do not generally seem to be able to make use of complex or detailed info from lengthy lectures, not in the same way a scientist may make active use of understanding gained from a theoretical talk.

Ability to use a language seems to be more of a skill you learn by trying to do it, akin to riding a bicycle, than an amount of data you learn and then try to apply.

Language learners seem to need a number of things beyond simply listening to explanations. Amongst other things, they need to gain exposure to comprehensible samples of language, not just the teacher’s monologues, and they need chances to play with and communicate with the language themselves in relatively safe ways.

If any of these things are to happen, it seems likely class working styles will involve a number of different Moses and not only an upfront lecture by the teacher.

Of course, a lot of teaching work will involve standing and talking to or with students, but a teaching style predominantly uses this technique’s likely to be inappropriate.

Students need to talk themselves; they need to communicate with a variety of people; they need to do a variety of different language-related tasks; they need feedback on how successful or not their attempts at communication have been.

So what’s a teacher for? Short answer: to help learning to happen. Methodology such as we discuss in this book’s what a teacher uses to try and reach the challenging goal.

Task 1.7 Learners’ expectations of teachers - Imagine you’re about to start studying a new language in a class with other beginners.

Consider your expectations of the teacher’s role. What’re some of the general things they can do to assist your learning?

The subject matter of ELT - What exactly are we teaching? What’s the subj matter of language teaching?

An outsider may imagine the content would comprise two major elements, namely knowledge of the language’s grammar and knowledge of lots of vocab.

Of course, these do form an important part of what’s taught/learned, but it’s important to realize someone learning a language needs far more than in the head knowledge of grammar and vocab in order to be able to use language successfully.

In staff rooms, you’ll find teachers typically classify the key subj matter of language teaching into language systems and language skills.

There’re other important subj areas as well, including learning better ways of learning, exam techniques, working with and learning about other people.

Language systems - We can analyze a sentence such as Pass me the book in different ways. We could consider:

the sounds (phonology)

the meaning of the individual words or groups of words (lexis or vocab)

how the words interact with each other within the sentence (grammar)

the use to which the words are put in particular situations (function).

If we extend our language sample into a complete (short) convo, eg.

A: Pass me the book.

B: Mary put it in her bag.

then we’ve an additional area for analysis, namely the way communication makes sense beyond the individual phrase or sentence, analyzing how the sentences relate or don’t relate to each other known as discourse.

Fig. 1.6 shows a brief analysis of the language sample from each of these viewpoints.

So we’ve five language systems, though all are simply different ways of looking at the same thing. If we’re considering teaching an item of language, one thing we need to decide is which system(s) we’re going to offer our learner info about.

We may plan a lesson focused on only one area, eg grammar, or we may deal with two, three or more. An ex of a commonly combined systems focus in many language lessons would be:

grammar+pronunciation+function

(ie how the language is structured, how to say it and how it’s used).

Phonological /pas mi: ds'buk/ or /pas m:i he 'buk/

The stress is probably on book, but also possible with different meanings on Pass or me.

Lexical Pass = give; hand over; present

me = reference to speaker

the book = object made of paper, containing words and/or pictures and conveying info

Grammatical Verb (imperative) + first person object pronoun + definite article + noun

Function A request or order

Discoursal Although not a direct transparent answer to the request, we can still draw a meaning from this reply. The word it, referring to the book, helps us to make a connections to the request. Assuming Mary’s put it in her bag is intended as a genuine response to the request, it may suggest a reason why the book can’t be passed (eg I can’t because Mary took the book with her). In order to fully understand the meaning, we’d need to know more about the situational context (ie who’s talking, where, etc) and more about the surrounding convo (ie what knowledge’s assumed to be known or shared between the speakers).

Fig. 1.6 Analysis of a language sample

Task 1.8 Recognizing language systems - Imagine you intend to do some teaching using this piece of language: Can you play the guitar? Match some points you may focus on with the correct system name:

1 the construction can + pronoun

2 the meaning of play and guitar

3 variations eg strong /kan ju:/ vs weak /kan je/, stress on guitar, etc.

4 asking about ability

5 typical question-and-reply sequences containing this language

a function

b discourse

c lexis

d grammar

e pronunciation

Answers

1 d 2c 3e 4a 5b

Task 1.9 Distinguishing language systems - You want to teach a lesson contrasting two potentially confusing areas of language. Classify each of the following teaching points as G for grammatical, L for lexical, P for phonological, F for functional.

Ex.: house compared to flat = L (lexical)

1 I went to Paris compared to I’ve been to Paris

2 Lend us a fiver compared to Could you possibly lend me $5?

3 library compared to bookshop

4 woman compared to women

5 Sorry compared to Excuse me

6 hut compared to hat

7 impotent compared to important

8 some compared to any

Answers

1 G 2 F 3 L 4 G/P 5 F 6 P (changing vowel sound)

7 P (changing word stress) / L 8 G

Language skills - As well as working with the language systems (which we can think of as what we know, ie ‘up-in-the-head’ knowledge), we also need to pay attention to what we do with language.

These are the language skills. Teachers normally think of there being four important macro language skills: listening, speaking, reading, writing.

Listening and reading are called receptive skills (the reader or listener receives info but doesn’t produce it); speaking and writing are the productive skills.

Skills are commonly used interactively and in combo rather than in isolation, esp speaking and listening. It’s arguable other things (eg thinking, using memory and mediating) are also language skills.

Language systems Language skills

knowing doing

Phonology Productive | Speaking

Lexis | Writing

Grammar Receptive | Reading

Function | Listening

Discourse

Fig. 1.7 Language systems and skills

The main four skills are referred to as macro due to any one of them being able to be analyzed down to smaller micro skills by defining more precisely what exactly’s being done, how it’s being done, the genre of material, etc. For ex:

Macro skills Listening

Some micro Understanding the gist of what’s heard, eg Who’s talking?

skills Where are they? What are they doing? What’s their relationship? How do they feel?

Understanding precise info re quantity, reference, numbers, prices, etc when listening to a business telephone call where a client wants to place an order.

Compensating for words and phrases not heard clearly in an informal pub convo by hypothesizing what they are, based on understanding of the content of the rest of a convo and predictions of likely content.

Task 1.10 Listening to a radio weather forecast - Consider briefly how you listen to the radio weather forecast in your own language.

What would be different if you listed to one in a foreign language you have been studying for a year or so?

Commentary - Many of the skills we hav win our own native language are directly transferable to a foreign language, but we do need practice in a number of areas.

For ex, I can listen to a weather forecast in my own language: I only half-listen until I hear the forecaster mention my part of the country, then I switch on and concentrate to catch the key phrases about it, then switch off again, but when I listen to a weather forecast in a foreign country in a different language, I’ll have problems, even if I know all the words and all the grammar the forecaster uses.

Trying to decipher words in the seemingly fast flow of speech, trying to pick out what’s important and what’s not, is a skill which needs to be practiced; it’s work which needs attention it its own right, quite apart from the study of the grammar and vocab involved.

The importance of skills work - Don’t underestimate the importance of skills work. Not every lesson needs to teach new words or new grammar.

Lessons also need to be planned to give students opportunities to practice and improve their language skills. Skills work is not something to add in at the end of a five-year course in English.

There’s no need to wait for extensive knowledge before daring to embark on listening and speaking work. On the contrary, it’s something so essential it needs to be at the heart of a course from the start.

Even a beginner with one day’s English will be able to practice speaking and listening usefully. For more on skills work see CH9 and CH10.

A purpose-based view of course content - Another way of looking at possible course content is to consider the communicative purposes students need language for.

The Common European Framework see in later CH, focuses on what learners can do with language. For ex, can an individual learner successfully attend company planning meetings?

Or take notes in physics lectures at uni? An analysis of such can-do requirements suggests a different kind of course content, one based around students planning, understanding and reflecting on tasks which reflect these real-life purposes.

This course content would clearly include systems and skills work, but would be organized around this key idea of real-world uses.

Changes of emphasis - Traditionally, language teaching concentrated on grammar and vocab reinforced by reading and writing.

The reading and writing’s primarily to help teach the grammar and vocab rather than help improve the students’ skills in reading or writing.

Teaching approaches have varied over the years based mainly around oral language practice thought repetition and drilling.

Nowadays, most interest is expressed in work on all language systems and skills, particularly emphasizing listening and speaking, due to everyday life we often do far more speaking and listening than reading and writing.

Grammar ’s typically still the language system featuring most prominently on courses and course books, and at lower levels, also the are many students say they want or expect to study in most detail.

Often course books teach grammar with an emphasis on communication of meaning rather than purely mechanical practice.

Despite the continuing predominance of grammar, the implications of a more lexical oriented view of language are increasingly having an impact on material and task design.

The growing influence of the Common European Framework’s encouraged course designers, teachers, and examiners to increasingly see successful communication in real-world tasks as a more important goal than of accurate language use.

Task 1.11 Balancing systems and skills - Here are two teaching situations. What balance of systems and skills would make a useful course for these learners?

1 A 24-year-old Japanese learner has studied grammar at school for nine years; she can read and understand even complex texts well. She’s arrived in England to take a two-week intensive course.

In her placement test which was mainly multiple-choice grammar questions, she scored very well, but at the initial interview, she had trouble answering even simple questions about herself and often haltingly asked the interviewer to repeat the question.

2 A group of 3 undergrads science students have enrolled for an English course at a language school in the Czech Republic. They know no English at all.

Commentary

1 The Japanese learner clearly needs a lot of work on the skills of listening and speaking. As she knows a lot of grammar, the course could concentrate on helping her activate this passive knowledge; the main thrust of the work could be on realistic listening and speaking activities to promote fluency and improve communicative abilities.

2 Most beginners need a balanced course which intro’s them to the five systems and four skills. In their future careers, these science learners may well need to read and write in English a lot, but may also need to visit other countries, listen to conference speeches and give them, greet visiting scientists, etc. If they’re likely to meet English-speaking and listening, alongside work to help them read and write more effectively.

The communicative purpose of language learning - It’s important to remember no one area of skills or language systems exists in isolation: there can be no speaking if you don’t have the vocab to speak with; there’s no point learning words unless you can do something useful with them.

The purpose of learning a language’s usually to enable to take part in exchanges of info: talking with friends, reading instructions on a packet of food, understanding directions, writing a note to a colleague, etc.

Sometimes traditional teaching methods have seemed to emphasize the learning of language systems as a goal in its own right and failed to give learners an opportunity to gain realistic experience in actually using the language knowledge gained; how many students have left school after studying a language for years, unable to speak an intelligible sentence?

Task 1.12 Recognizing skills or systems aims - Every activity is likely to involve some work on both language systems and skills, though, usually, the aim’s directed more to one area than the other.

In the following list, classify each activity as ‘mainly skills’ or ‘mainly systems’ by ticking the appropriate box. Then decide which skills or which language systems are being worked on.

Mainly systems Mainly skills

1 You write a grammar exercise on the board which learners copy and then do.

2 Learners read a newspaper article and then discuss the story with each other.

3 Learners underline all past simple verb forms in a newspaper article.

4 Learners chat with you about the weekend.

5 Learners write an imaginary postcard to a friend, which you then correct.

6 Learners write a postcard to a friend, which is posted uncorrected.

7 You use pictures to teach ten words connected with TV.

8 You say ‘What tenses do these people use?’ Learners than listen to a recorded convo.

9 You say ‘Where are these people?’ Learners then listen to a recorded convo.

Commentary - In activity 1, the students do read and write, but use few of the skills which we need when we read and write in our normal life.

Certainly, comprehending the teacher’s handwriting and forming one’s own letters on the page may be quite demanding for some students, esp for those whose native language doesn’t use roman script, but beyond this, the activity’s main demand is on using grammar correctly.

Activity 2 involves the skills of reading and speaking in ways very similar to those in the outside world. Vocab and grammar will be encountered in the reading, but the main aim is for understanding rather than analysis and study.

Compare this with activity 3, where the same material’s used, but now with a specific grammar aim. Compare then with activities 5,6, and 8,9. The aim in activity 4 is to encourage fluent speaking.

The aim in activity 7 is to teach some vocab, and the speaking and listening and writing involved are of less importance.

Other areas that are part of language learning - The map of language systems and language skills is useful to keep in mind as an overview of the subj matter of English language teaching.

However, it may well be an over-simplification. Elsewhere in this book, you’ll come across some doubts about it, for ex, when we ask if grammar is more fruitfully viewed as a skill students need practice in using rather than as a system to learn, and of course, there’s more to English language teaching than simply the language itself:

Students may e learning new ways of learning: for ex, specific study skills and techniques.

They’ll also be learning about the other people in their class, and exploring ways of interacting and working with them.

They may be learning about themselves and how they work, learn, get on with other people, cope with stress, etc.

They may be learning a lot about the culture of the countries whose language they’re studying.

They may be learning how to achieve some specific goal, for ex, passing an exam, making a business presentation at an upcoming conference.

They may also be learning about almost anything else. The subj matter of ELT can encompass all topics and purposes we use language to deal with.

Many teachers seem to become quite knowledgeable on the environment, business protocol, etc. This is probably what keeps the job interesting!

Some course book texts seem to achieve nearly legendary status amongst teachers! (As a teacher who’s been in the business a few years if they know anything about a nun called Sister Wendy!)

If we start using English in class to do more than simple mechanical drills, then the subj matter becomes anything we may do with language, any topic which may be discussed with English, any feelings which may be expressed in English, any communication we may give or receive using English.

The people who use the language in class, and their feelings, are therefore, also part of the subj matter. This may be a little daunting and lead you to keep the uses of language in class at a more mechanical, impersonal level, without allowing too much ‘dangerous’ personal investment in what’s said or heard.

This seems sad to Scrivener; he believes we need to give our students chances to feel and think and express themselves in their new language.

Methods - Task 1.13 Your own teaching method

1 Would you be able to name the teaching method(s) you use?

2 What’re the key features of it and what’re its underlying principles?

Commentary - A method’s a way of teaching. Your choice of method is dependent on your approach, ie what you believe about:

what language is;

how people learn;

how teaching helps people learn.

Based on such beliefs, you’ll then make methodological decisions about:

the aims of a course;

what to teach;

teaching techniques;

activity types;

ways of relating with students;

ways of assessing.

Having said this, some methods exist without any apparent sound theoretical basis!

Some well-known methods and approaches

including:

The Grammar-Translation Method - Much traditional language teaching in schools worldwide used to be done in this way and it’s still the predominant class method in some cultures.

The teacher rarely uses the target language. Students spend a lot of time reading texts, translating them, doing exercises and tests, writing essays. There’s relatively little focus on speaking and listening skills.

The Audio-Lingual Method - Although based on largely discredited theory, the techniques and activities continue to have a strong influence over many classes.

It aims to form good habits through students listening to model dialogues with repetition and drilling but with little or no teacher explanation.

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) or Communicative Approach (CA) - This is perhaps the method or approach most contemporary teachers’d subscribe to, despite the fact it’s widely misunderstood and misapplied.

CLT is based on beliefs which learners will learn best if they participate in meaningful communication. It may help if we distinguish between a stronger and a weaker version of CLT.

With strong CLT students learn communicating, ie doing communication tasks with a limited role for explicit teaching and traditional practice exercises.

In contrast, with weak CLT students learn through a wide variety of teaching, exercises, activities, and study, with a bias towards speaking and listening work. Most current course books reflect a version of weak CLT.

Total Physical Response (TPR) - A method mainly useful with beginner and lower-level students. Learners listen to instructions from the teacher, understand and do things in response, without being required to speak until they’re ready, see in CH ahead.

Community Language Learning (CLL) - A method based around use of the learners’ first language and with teacher help in mediating.

It aims to lower anxiety and allow students to communicate in a more genuine way than is typically possible in classes.

The natural approach - a collection of methods and techniques from many sources, all intended to provide the learner with natural comprehensible language so the learner can pick up language in ways similar to a child learning their first language.

Task-Based Learning (TBL) - A variant of CLT (see above) which bases work cycles around the prep for doing of, and reflective analysis of tasks which reflect real-life needs and skills.

The Silent Way - This method requires the learner to take active ownership of their language learning and to pay great attention to what they say.

Distinctive features include the relative restraint of the teacher (who’s not completely silent!) and the use of specially designed wall charts.

The use of Cuisenaire rods in mainstream ELT arose from this method, see CH below.

Person-centred approaches - Any approach which places learners and their needs at the heart of what’s done. Syllabus and working methods won’t be decided by the teacher in advance of the course, but agreed between learner and teacher.

Lexical approaches - On the back of new discoveries about how languages really used, esp the importance of lexical chunks in communication, proponents suggest traditional present-then-practice methods are of little use and propose a methodology based around exposure and experiment.

Dogme - back-to-basics approach where teachers aim to strip their craft of unnecessary technology, materials and aids and get back to the fundamental relationship and interaction of teacher and student in class.

Some schools, or individual teachers follow one of these named methods or approaches. In naming a method, a school suggests all or most work will fit a clearly stated, recognizable and principled way of working.

Other schools sometimes advertise a unique named method of their own, eg the Cambridge Method. These are usually variations on some of the methods listed above, or not a method at all but something else, eg simply the name of the course book series being used, eg. the Headway Method, a way of dividing levels according to a familiar exam system, or an eclectic contemporary lucky dip.

Personal methodology - Despite the grand list of methods above, the reality is very few teachers have ever followed a single method it its entirety, unless they work in a school demanding they do and carefully monitors adherence.

Many teachers nowadays would say they don’t follow a single method. Teachers don’t generally want to take someone else’s prescriptions to class and apply them.

Rather they work out for themselves what’s effect in their own classes. They may do this in a random manner or in a principled way, but what they slowly build over the years is a personal methodology of their own, constructed from their selection of what they consider to be the best and most appropriate of what they’ve learned about.

The process of choosing items form a range of methods and constructing a collage methodology is sometimes known as principled eclecticism.

*******First lessons - hints and strategies *********

Key hints when planning your first lessons

Use the course book, if there is one Don’t feel you have to come up with studding original lesson ideas and creative new activities.

If you’ve a course book, then you have an instant source of material. It’s fine to rely on the longer experience of the course book writers and do the lesson exactly as it’s written.

Take your time before the lesson to read carefully through the unit, and give the same attention to the Teacher’s Book, if you have access to one.

There’s a reasonable chance you’ll end up with a workable lesson. Many teachers also use ideas books, known as recipe books, which do exactly what the nickname suggests - give you everyone needed to know to be able to walk into class with the right ingredients to cook up a good activity.

A lesson is a sequence of activities Think of the lesson as a series of separate but linked activities.

Your first planning job is to select some appropriate activities. Read CH2 and be clear what an activity is and how you can organize it in class.

Learn something about your students If possible, talking to other teachers and find out something about the class and the people in it.

Plan student-focused activities Don’t plan first lessons will put you upfront in the spotlight feeling the need to burble. It leads to panic and muddle. Plan activities which are based on the following route map:

1 Lead-in, a brief intro to the topic, eg you show a picture to the class and invite comments.

2 Set up the activity, ie you give instructions, arrange the seating, etc.

3 Students do the activity in pairs or small groups while you monitor and help.

4 Close the activity and invite feedback from the students.

Steps 1,2, and 4 should take relatively little time. The heart of this sequence is Step 3. This route-map lesson plan is looked at in more detail in CH2.

Make a written plan of the running order of your activities Write out a simple list showing the activities in order.

You don’t need to include a lot of detail, but make sure you have a clear idea of your intended sequence of stages, perhaps with estimated timings.

Consider aims Thinks about what students will get from your lesson, ie what’s the point of them spending their time in this lesson?

Fluency or accuracy? Decide for each stage in the lesson if you’re mainly working on fluency or accuracy - this is a key choice for many activities, see CH9

Get the room ready; get yourself ready If the timetabling and organization of your school allows it, take time before any students arrive to make sure everything’s ready before the class starts.

Make sure the room’s set up as you wish, eg how’ll you arrange seating?. Make sure you have everything you need, chalk or board pens, don’t expect them to magically be there!

And most importantly, feel what it’s like to be in the room. Start to settle into it, to exercise ownership over it. For the length of the lesson it’s your space.

Have at least one emergency activity! - Prepare your own personal emergency ‘Help, I’ve run out of things to do and still have five minutes left’ activity, eg. A word game, an extra photocopied game, etc. Keep this and add more emergency ideas day by day.

Key hints when starting to teach

Talk to the students as they come into the room - Don’t hide or do not-really-necessary ‘business’ while you wait for all students to arrive.

This quickly builds up a tension and distance between you and the students and makes the start of the lesson much more demanding.

Instead, think of the lesson as starting from the first moment a student arrives in the room. You can calm your own nerves and break the ice with students very quickly by chatting with each of them as they come into the room.

Try sitting with them, even just for a minute or two, rather than standing in front of them. Welcome them. Ask them their names.

You’ll immediately start to learn something about them as real people rather than as generic students, and you’ll find you can start to relax a little.

Learn names as soon as possible - There’s a huge difference in comfort levels if you know people’s names. They stop being scary anon. entities and start to become humans.

In class it’s a very important teacher skill, and you should aim to internalize names as soon as possible. It’s a bit embarrassing if you have to ask people their names over and over. Don’t say I’m bad at remembering names.

Make learning names quickly and accurately your first priority. If for any reason the pronunciation of names is a problem, take time to get the sounds right; if you’re teaching in another country, maybe get a local speaker to help you.

1 As you ask each student for their name, write it down on a mini-sketch-map of the class. When you have all the names, test yourself by covering the map, looking at the class and saying the names to yourself.

Check and repeat any names you don’t yet know.

2 Ask students to make a small place card for themselves by folding a piece of paper in half. They should write their names on this so every name’s visible to you at the front.

As the lesson proceeds, turn individual cards around when you think you know the student’s name. Some teachers use cards like these through whole courses; Scrivener finds it lazy.

This strategy’s to help you learn names, not sub for learning them.

3 Use name games from CH15. If it’s not only you the teacher, who’s new, but your students are also new to each other, then using some of these name-game activities will definitely be a good idea.

Be yourself - Don’t feel being a teacher means you have to behave like a teacher. As far as possible, speak in ways you normally speak, respond as yourself rather than as you think a teacher should respond.

Students, whether children, teens, or adults, very quickly see through someone who’s role playing what they think a teacher should be. Authenticity in you tends to draw the best out of those you’re working with.

Teaching doesn’t mean ‘talking all the time’ - Don’t feel when you’re ‘in the spotlight’, you’ve to keep filling all the silences. When you’re teaching a languages he priority is for the learners to talk, rather than the teacher.

Start to notice the quantity of your own talk as soon as possible - and check out how much’s really useful. High levels of teacher talk is a typical problem for new teachers.

Teaching doesn’t mean ‘teaching’ all the time - Don’t feel being a teacher mean you have to be doing things all the time. It may feel a little odd, but it really is quite ok to sit down and do nothing when students are working on a pair or group task.

There’re times when your help will actually be interference. Take the chance to recover from your exertions, check your notes and enjoy watching your class at work.

Slow down - A large number of new teachers tend to do things much too fast. They often seriously underestimate how difficult things are for students, or are responding to a fear students will find things boring.

Learning to really slow down takes time, but it’s worth bearing in mind from your first lesson onwards. For ex, don’t ask a question and then jump straight in again due to thinking they can’t answer it.

Instead, allow three times the length of time you feel students need, this is sometimes called wait time.

Key hints for starting to teach better (once you’ve got past the first few classes)

Turn your radar on - You’re likely to be a little self-focused during your early lessons, but as soon as you can, start to tune in more to the students. Start to ask for comments and brief feedback on things you do.

Watch the students at work and learn to notice what’s difficult, what’s easy, what seems to engage, what seems boring. Study your students.

Don’t teach and teach… Teach then check - Practice’s more important than input. Checking what students have understood and testing if they can use items themselves is usually more important than telling them more about the new items.

Don’t do endless inputs. Teach a very little amount… then check what students have taken in. Give students the opportunity to try using the items, eg. A little oral practice, a written question or two, or even simply repeat.

(Here’s a rule-of-thumb ratio to experiment with: input 5%, checking and practice 95%.)

Are you teaching the class… or one person? - When you ask questions / check answers, etc, are you really finding out if they all know the items… or is it only the first person to call out?

If one person says an answer, does this mean they all know? What about the others? How can you find out?

CH2 Classroom activities

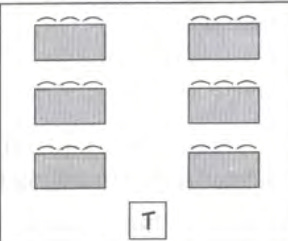

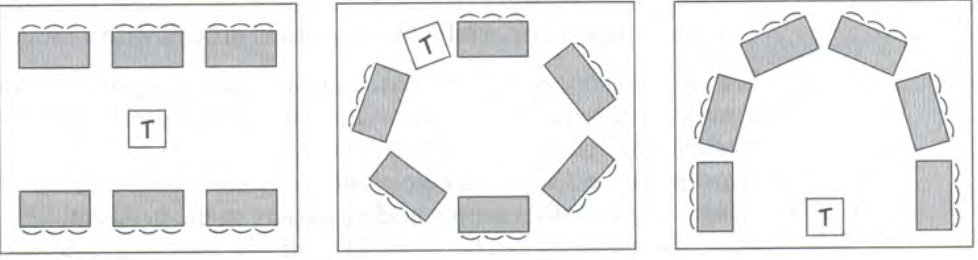

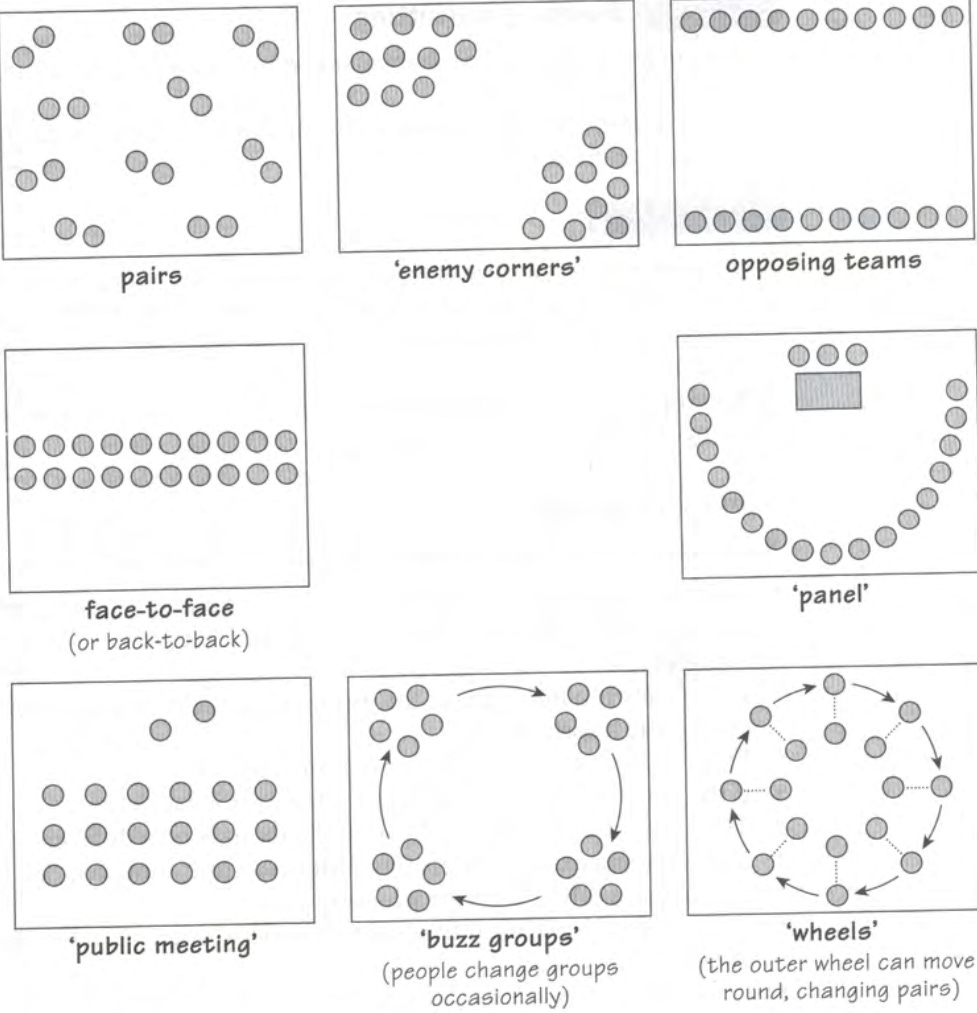

This CH looks at some things you need to consider when you first start planning and running activities. We also look at some basic class management issues, such as how to arrange students in working pairs on groups.

Planning an activity - the basic building block of a lesson’s the activity or task. We’ll define this fairly broadly as ‘something learners do which involves them using or working with language to achieve some specific outcome’.

The outcome may reflect a ‘real-world’ outcome, eg. learners role play buying train tickets at the station, or it may be a purely ‘for-the-purposes-of-learning’ outcome, eg. learners fill in the gaps in twelve sentences with present perfect verbs. By this def, all of the following are activities or tasks:

Learners do a grammar exercise individually then compare answers with each other in order to better understand how a particular item of languages formed.

Learners listen to a recorded convo in order to answer some questions, in order to become better listeners.

Learners write a formal letter requesting info about a product.

Learners discuss and write some questions in order to make a questionnaire about people’s eating habits.

Learners read a newspaper article to prepare for a discussion.

Learners play a vocab game in order to help learn words connected with cars and transport.

Learners repeat a number of sentences you say in order to improve their pronunciation of them.

Learners role play a shop scene where a customer has a complaint.

Some things happen in the class aren’t tasks. For ex, picture a room where the teacher’s started spontaneously discussing in a lengthy or convoluted manner the formation of passive sentences.

What’re students doing which has an outcome? Arguably, there’s an implied task, namely students should ‘listen and understand’, but by not being explicit, there’s a real danger learners aren’t genuinely engaged in anything much at all.

This is a basic, important and often overlooked consideration when planning a lesson. As far as possible, make sure your learners have some specific thing to do, whatever the stage of the lesson.

Traditional lesson planning has tended to see the lesson as a series of things the teacher does. By turning it round and focusing much more on what the students do, we’re likely to think more about the actual learning may arise and create a lesson is more genuinely useful, and if you plan everything in terms of what the students will do, you may find you worry less about what the teacher has to do!

Even for stages when you’re ‘presenting’ language, be clear to yourself what its students are supposed to be doing and what outcome it’s leading to.

Think of a complete lesson as being a coherent sequence of such learner-targeted tasks.

Task 2.1 Using course book material - Here’s some material from a student course book.

Speaking

Which of these ‘firsts’ do you remember best?

your first home your first friend your first hero your first crush

your first date your first love your first English lesson your first kiss

your first dance your first holiday your first broken heart

In using it as the basis for a class activity, which of the following working arrangements would be possible?

Students think and then write answers on their own.

Students prepare a short monologue statement of their own views which they then present to the whole class.

A whole-class discussion of ideas and answers.

Pairwork discussion.

Small-group work.

Students walk around and mingle with other students.

Written homework.

Commentary - Even a simple task like this can be used in a variety of ways, and all the suggested uses are possible.

Combos of ideas are also possible; for ex, students could first think on their own for a few minutes and then compare in pairs.

Whatever you choose, there’re then further options as to how you do the task; for ex, you could ask students to compare, discuss and question each other’s views or to reach a consensus compromise solution.

These variations lead to two very different types of speaking activity. More variations are possible when considering the stages immediately precede or follow the activity.

Your choices as to how the task will be done depend partly on the aim of the activity, ie. what you want students to get out of it.

Teacher options - bear in mind, even where course book tasks include explicit instructions such as Compare answers in pairs or Work in small groups, you always have the option as a teacher to give a different organizational instruction.

For ex, you may feel a ‘work in pairs’ exercise may be more interesting done in small groups, and even if you follow the book’s instruction, you still have the possibility of manipulating the organization a little, for ex:

tell each student who they must work with, eg ‘Petra, work with Cristina’;

the students can choose partners for themselves;

the pairings can be the result of some random game or humorous instruction, eg. Find someone whose shoes are a different color from your own.

The course book provides the raw material which only comes alive in class. You have important choices as to how to do this.

Fig. 2.1 Activity options (seen below) summarises some basic options you could consider for many basic short course book activities, eg. for short discussion tasks such as the ‘firsts’ task above.

What arrangements can you use? A few variations on the arrangements

Individual work Students talk together and write nothing; they’re permitted to write.

Pairwork You choose pairs; students choose pairs; pairs are randomly selected, eg from a game; face to face; back to back; across the room, shouting’ communicating in writing only.

Small groups, 3 - 6 people Groups have a secretary, note-taking duty; groups have an appointed leader; memberships of groups’s occasionally rearranged; groups are allowed to send ‘ambassadors’ / ‘pirates’ to other groups, to compare / gain / steal ideas

Large groups (as above)

Whole class: mingle, all stand up, Students may only talk to one other person at a time; groups may meet walk around, meet and talk up to max of 3 / 4 / 5 people; time limits on meetings; you ring bell / stop background music, etc to force rearrangements

Whole class: plenary The convo / activity’s managed by you / a student / a number of students; whole-class work with brief ‘buzz’ intervals of pairwork / small- group discussion.

A few more variations for running an activity

Do it at speed, with a very tight time limit.

When a group finishes, they disperse and join other groups.

Each person makes a quick answer which’s noted but not discussed; then, when all have spoken, the discussion begins, using the notes as a starting point.

Require compromise / consensus single answers.

Intro task by dictating instructions / problem, etc; individuals dictate answers back to the whole class.

Students prepare a report-back presentation summarizing their solutions.

Students prepare a role play dialogue incorporating their answers.

Students do the exercise as homework.

Activity route map - Here’s a basic route map plan for running a simple activity. In some bigger activities, there may be a number of clearly separate ‘sections’ within the task, in which case you’d go through Steps 3,4 and 5 a few times.

Before the lesson: familiarize yourself with the material and activity; prepare any materials or texts you need.

In class: lead-in / prepare for the activity.

Set up the activity (or section of activity), ie give instructions, make groupings, etc.

Run the activity or section: students do the activity, maybe in pairs or small groups while you monitor and help.

Close the activity or section and invite feedback from the students.

Post-activity: do any appropriate follow-on work.

Looking at each step in more detail:

Before the lesson

Familiarize yourself with the material and the activity.

Read through the material and any teacher’s notes.

Try the activity yourself.

Imagine how it’ll look in class.

Decide how many organizational steps are involved.

What seating arrangements / rearrangements are needed?

How long will it probably take?

Do the learners know enough language to be able to make a useful attempt at the activity?

What help may they need?

What questions may they have?

What errors, using the language, are they likely to make?

What errors, misunderstanding the task, are they likely to make?

What’ll your role be at each stage?

What instructions are needed?

How will they be given, explained, read, demo’d?

Prepare any aids or addt’l material.

Arrange seating, visual aids, etc.

Most importantly, you need to think through any potential problems or hiccups in the procedures. For ex, what’ll happen if you plan student work in pairs, but there’s an uneven number of students? Will this student work alone, or will you join in, or will you make one of the pairs into a group of three?

Lead-in / Preparation - this may be to help raise motivation or interest, eg discussion of a picture related to the topic, or perhaps to focus on language items, eg items of vocab, which may be useful in the activity.

Typical lead-ins are:

Show / draw a picture connected to the topic. Ask questions.

Write up / read out a sentence stating a viewpoint. Elicit reactions.

Tell a short personal anecdote related to the subj.

Ask students if they’ve ever been / seen / done, etc

Hand out a short text on the topic. Students read the text and comment.

Play ‘devil’s advocate’ and make a strong / controversial statement, eg I think smoking is very good for people, so students’ll be motivated to challenge / argue about.

Write a key word, maybe the topic name, in the centre of a word-cloud on the board and elicit vocab from students which is added to the board.

Setting up the activity

Organise the students so they can do the activity or section. (This may involve making pairs or groups, moving the seating, etc.)

Give clear instructions for the activity. A demo or ex is usually much more effective than a long explanation.

See Giving clear instructions and Demo-ing tasks teaching techniques on the DVD or research online

You may wish to check back the instructions have been understood eg, So, Georgi, what are you going to do first?

In some activities, it may be useful to allow some individual work, eg thinking through a problem, listing answers, etc, before the students get together with others.

Running the activity

Monitor at the start of the activity or section to check the task has been understood and students are doing what you intended them to do.

See Monitoring teaching technique on the DVD or research online

If the material’s well prepared and the instructions clear, then the activity can now largely run itself. Allow the students to work on the task without too much further interference. Your role now is often much more low-key, taking a back seat and monitoring what’s happening without getting in the way.

Beware of encumbering the students with unnecessary help. This is their chance to work. If the task’s difficult, give them the chance to rise to the challenge, without leaning on you. Don’t rush in to ‘save’ them too quickly or too eagerly. Though, having said this, remain alert to any task which genuinely proves too hard, and be prepared to help or stop it early if necessary!

Closing the activity

Allow the activity or section to close properly. Rather than suddenly stopping the activity at a random point, try to sense when the students are ready to move on.

If different groups are finishing at different times, make a judgement about when coming together as a whole class would be useful to most people.

If you want to close the activity while many students are still working, give a time warning, eg Finish the item you’re working on or Two minutes.

Post-activity - It’s usually important to have some kind of feedback session on the activity. This stage’s vital and is typically under-planned by teachers!

The students have worked hard on the task and it’s probably raised a number of ideas, comments and questions about the topic and about language.

Many teachers rely on an ‘ask the class if there’re any problems and field the answers on the spot’ approach. While this will often get you through, it can also lead you down dark alleys of confusing explanations and long-winded spontaneous teaching.

It can also be rather dull simply to go over things which’ve already been done thoroughly in small groups. So, for a number of reasons, it’s worth careful planning of this stage in advance, esp to think up alternatives to putting yourself in the spotlight answering a long list of questions.

Groups meet up with other groups and compare answers / opinions.

Students check answers with the printed answers in the Teacher’s Book, which you pass around / leave at the front of the room / photocopy and hand out, etc.

Before class, you anticipate what the main language problems will be and prepare a mini-presentation on these areas.