How to Teach English by Jeremy Harmer (CELTA course study material #3)

CH1 Learners

Reasons for learning The importance of student motivation

Different contexts Responsibility

Learner differences

Reasons for learning - All around the world people learn English for varying reasons, many learn due to having moved into a target-language community and they need to operate successfully within it.

A target-language community is a place where English is the national language, like Britain, Can, NZ, etc, or where it’s one of the main languages of culture and commerce, like India, Pakistan, Nigeria.

Some students need English for a Specific Purpose ESP, aka English for Special Purposes, may need to learn legal language, the language of tourism, banking or nursing, for ex.

A popular ESP is the teaching of business English, where students learn how to operate in English in the business world.

Many students need English for Academic Purposes EAP, in order to study at an English-speaking uni or college, or due to needing access to English-language academic texts.

Many people learn English due to thinking it’ll be useful in some way for international communication and travel.

The purposes students have for learning will have an effect on what it’s they want and need to learn, and as a result will influence what they’re taught.

Business English students will want to spend a lot of time concentrating on the language needed for specific business transactions and situations, for ex.

Students living in a target-language community will need to use English to achieve their immediate practical and social needs.

A group of nurses will want to study the kind of English they’re likely to have to use while they nurse.

Students of general English, including those studying the language as part of their primary and secondary education, will not have such specific needs, and so their lessons, and the materials which the teachers use, will almost certainly look different from those for students with more clearly identifiable needs.

Consideration of our students’ different reasons for learning is only one of many different learner variables, as we shall see below.

Different contexts for learning - English is learnt and taught in many different contexts, and in many different class arrangements. Such differences will have a considerable effect on how and what it is we teach.

EFL, ESL, and ESOL - For many years we’ve made a distinction between people who study English as a foreign language and those who study it as a second or other language.

It’s been suggested students of EFL tend to be learning so they can use English when traveling or to communicate with other people, who also speak English, from whatever country.

ESL students are usually living in the target-language community. The latter may need to learn the particular language variety of community (Scottish English, southern English from England, Australian English, Texan English, etc) rather than a more general language variety, ex. in below CH.

They may need to combine their learning of English with knowledge of how to do things in the target-language community, such as going to a bank, renting a flat, accessing health services, etc.

The English they learn, therefore, may differ from those studied by EFL students, whose needs aren’t so specific to a particular time and place.

However, this distinction begins to look less helpful when we look at the way people use English in a global context.

The use of English for international use, esp online, means many EFL students are in effect living in a global target-language community and so may be thought of ESL students instead!

Partly as a result of this we not tend to use the term ESOL, English for Speakers of Other Languages, to describe both.

Nevertheless, the context in which the language is learnt, what community they wish to be part of, is still of considerable relevance to the kind of English they’ll want and need to study, and the skills they’ll need to acquire.

Schools and language schools - A huge number of students learn English in primary and secondary classes around the world, they haven’t chosen to do this themselves, but learn due to English being on the curriculum.

Depending on the country, area and the school itself, they may have the advantage of the latest class equipment and info tech (IT), or they may, in some parts of the world, be sitting in rows in classes with a blackboard and no other teaching aid.

Private language schools tend to be better equipped than some gov’t schools, though this isn’t always the case. They’ll frequently have smaller class sizes, and crucially, the students in them may well have chosen to come and study. This’ll effect their motivation at the start of the process, seen below.

Large classes and one-to-one teaching - Some students prefer to have a private session with only them and the teacher. Commonly referred to as one-to-one teaching.

At the other end of the scale, English is taught in some environments to groups of over 100 students at a time. Gov’t school classes in many countries have up to 30 students, whereas a typical number in private language school lies somewhere between 8 and 15 learners.

Clearly the size of the class will affect how we teach. Pairwork and groupwork, further discussed below, are often used in large classes to give students more chances for interaction than they’d otherwise get with whole-class teaching.

In a one-to-one setting the teacher’s able to tailor the lesson to an individual’s specific needs, whereas with larger groups compromises have to be reached between the group and the individuals within it.

In large classes the teacher may well teach from the front more often than with smaller groups, where mingling with students when they work in pairs, etc may be much more feasible and time-efficient.

In-school and in-company - The vast majority of language classes take place in edu’l institutions as well as colleges and uni’s.

In such situations teacher have to be aware of school policy and conform to syllabus and curriculum decisions taken by whoever is responsible for the academic running of the school.

There may well be learning outcomes which students are expected to achieve, and students may be preparing for specific exams.

A number of companies also offer language classes and expect teachers to go to the company office or factory to teach.

Here the class may not be quite as appropriate as those which’er special designed for teaching and learning, but more importantly, the teacher may need to negotiate the class content, not only with the students, but also with whoever is paying for the tuition.

Real and virtual learning environments - Language learning has traditionally involved a teacher and a student or students being in the same physical space, now we have the internet, and some of the issues for both real and virtual learning environments are the same.

Students still need to be motivated and we still need to offer help in this area. As a result, the best virtual learning sites have online tutors who interact with their students via email or online chat forums.

It’s also possible to create groups of students who’re all following the same online program, and who can therefore ‘talk’ to each other in the same way, electronically, but despite these interpersonal elements, some students find it more difficult to sustain their motivation online than they may as part of a real learning group.

Virtual learning’s significantly different from face to face classes, firstly students can attend lessons when they want for the most part, though real-time chat forums have to be scheduled, rather than when lessons are timetabled, as in schools.

Secondly, it no longer matters where the students are since they can log on from any location in the world. Online learning may have these advantages, but some of the benefits of real learning environments are less easy to replicate electronically.

These include the physical reality of having teachers and students around you when you’re learning so you can see their expressions and get messages from their gestures, tone of voice, etc.

Many learners will prefer the presence of real people to the sight of a screen, with or without pictures and video. Some communication software, like instant messengers and Skype/Zoom, allows users to see each other on the screen as they communicate, but this is still less attractive, and considerably more jerky, than being face to face with the teacher and fellow students.

Of course, whereas in real learning environments learning can take place with very little technical equipment, virtual learning relies on good hardware and software, and effective internet connections.

Although this book will look at the uses of internet and IT apps, it’s not primarily concerned with the virtual learning environment, preferring instead to concentrate situations where the teachers and learners are usually in the same place at the same time.

Learner differences - Whatever their reasons for learning, or circumstances it takes place, it’s sometimes tempting to see all students as being more or less the same.

Yet there’re marked differences, not only in terms of age and level, but also in terms of different individual abilities, knowledge and preferences. We’ll examine some of these differences in this section.

Age - Learners are often described as children, young learners, adolescents, young adults, or adults. Within education, the term children is generally used for learners between the ages of about 2 -14.

Students described as young learners between the ages of about 5 to 9, and very young learners are usually between 2 - 5.

At what ages it’s safe to call students adolescents is often uncertain, since it’s bound up with physical and emotional changes rather than chronological age.

However, this term tends to refer to students from about 12-17, whereas young adults are generally between 16-20. We’ll look at 3 ages: children, adolescents and adults.

However, we need to remember there’s a large degree of individual variation in the ways in which different children develop. The descriptions following must be seen as generalizations only.

Children - We know children don’t just focus on what’s being taught, but also learn all sorts of other things at the same time, taking info from whatever is going on around them.

We know seeing, hearing, and touching are only as important for understanding as the teacher’s explanation.

We’re conscious the abstraction of say, grammar rules, will be less effective the younger the students are, but we also know children respond well to individual attention from the teacher and are usually pleased to receive teacher approval.

Children usually respond well to activities focusing on their lives and experiences, but a child’s attention span, their willingness to stay rooted in one activity’s often fairly short.

A crucial characteristic of young children’s their ability to become competent speakers of a new language with remarkable facility, provided they get enough exposure to it.

They forget languages with equal ease. This language-acquiring ability’s steadily compromised as they head towards adolescence.

Adolescents - One of the greatest differences between adolescents and young children’s these older children’ve developed a greater capacity for abstract thought as they’ve grown up.

In other words, their intellects are kicking in, and they can talk about more abstract ideas, teasing out concepts in a way which younger children find difficult.

Many adolescents readily understand and accept the need for learning of a more intellectual type. At their best, adolescent students have a great capacity for learning, enormous potential for creative thought and a passionate commitment to things which interest them.

Adolescence is bound up with a search for identity and a need for self-esteem. This is often the result of the students’ position within their peer group rather than being the consequence of teacher approval.

Adults - Older learners often but not always have a wider range of life experiences to draw on, both as individuals and as learners, than younger students do.

They’re often more disciplined than adolescents and apply themselves to the task of learning even when it seems fairly boring.

They often have a clear understanding of why they’re learning things, and can sustain their motivation, see below, by perceiving and holding on to long-term learning goals.

On the other hand, adult learners come with a lot of previous learning experience which may hamper their progress. Students who’ve had negative learning experience in the past may be nervous of new learning.

Students used to failure may be consciously or subconsciously prepared for more failure. Older students who’ve got out of the habit of study may find classes daunting places.

They may also have strong views about teaching methods from their past, which the teacher’ll have to take into account.

Due to student at different ages having different characteristics, the way we teach them will differ, as well. With younger children we may offer a greater variety of games, songs and puzzles than we would do with older students.

We may want to ensure there’re more frequent changes of activity. With a group of adolescents we’ll try to keep in mind the importance of a student’s place within his or her peer group and take special care when correcting or assigning roles within an activity etc. Our choice of topics will reflect their emerging interests.

One of the recurring nightmares for teachers of adolescents, is we may lose control of the class. We worry about lessons slipping away from us, and which we can’t manage due to the students not liking the subj, each other, the teacher or the school, or sometimes only due to feeling like misbehaving, or due to issues in their life outside the class affecting their behavior and outlook on life.

Yet teens are not the only students who sometimes exhibit problem behavior, the type which causes a problem for the teacher, the student themselves, and maybe the others in class.

Younger children can cause difficulties for the teacher and class, as well. Adults can also be disruptive and exhausting.

They may not do it in the same way as younger learners, but teachers of adults can experience a range of behaviors such as students who resist the teacher’s attempts to focus their attention on the topic of the lesson and spend the lesson talking to their neighbors, or who disagree vocally with much of what the teacher or their classmates are saying.

They may arrive late for class or fail to do any homework, and whatever the causes of this behavior, a problem’s created. Teachers need to work both to prevent problem behavior, and to respond to it appropriately if it occurs.

We’ll discuss how the teacher’s behavior can inspire the students’ confidence and cooperation seen below, and we’ll discuss what to do if students exhibit problem behavior in a coming CH.

Learning styles - All students respond to various stimuli, such as pics, sounds, music, movement, etc, but for most of them, and us, some things stimulate them into learning more than other things.

The Neuro-Linguistic Programming model, often called NLP, takes account of this by showing how some students are esp influenced by visual stimuli and are therefore likely to remember things better if they see them.

Some students, on the other hand, are esp affected by auditory input and respond very well to things they hear. Kinaesthetic activity’s esp effective for other learners, who seem to learn best when they’re involved in some kind of physical activity, such as moving around, or rearranging things with their hands.

The point is although we’ll respond to all of these stimuli, for most of us, one or other of them, visual, auditory, kinesthetic, is more powerful than the others in enabling us to learn and remember what we have learnt.

Another way of looking at student variation’s offered by the concept of Multiple Intelligences. In this formulation, and of people who’ve followed and expanded these theories, we’ll have a number of different intelligences, math, musical, interpersonal, spatial, emotional, etc.

However, while one person’s math intelligence may be highly developed, their interpersonal intelligence, the ability to interact with and relate to other people, may be less advanced.

What these two theories tell us from their different standpoints, is in any one class we have a number of different individuals with different learning styles and preferences.

Experienced teachers know this and try to ensure different learning styles are catered for as often as possible. In effect, this means offering a wide range of different activity types in our lessons in order to cater for individual differences and needs.

Nevertheless, we need to find out whether there’re any generalizations which’ll help us to encourage habits in students which’ll help all of them. We may say, for ex, homework is good for everyone and so is reading for pleasure, see CH7.

Certain activities, such as many of the speaking activities in CH9 are good for all students in the class, though the way we organize them, and the precise things we ask students to do may vary for exactly the reasons we’ve been discussing.

Levels - Teachers of English generally make three basic distinctions to categorise the language knowledge of their students: beginner, intermediate, and advanced. Broadly speaking, beginners are those who don’t know nay English and advanced students are those whose level English is competent, allowing them to read unsimplified factual and fictional texts and communicate fluently.

Between these two extremes, intermediate suggests basic competence in speaking and writing and an ability to comprehend fairly straightforward listening and reading.

However, as we’ll see, these are rough and ready labels whose exact meaning can vary from institution to school. Other descriptive terms are also used in an attempt to be more specific about exactly what kind of beginner, intermediate or advanced students we’re talking about.

A distinction’s made between beginners, students who start a beginners’ course and not heard virtually any English, and false beginners to reflect the fact the latter can’t really use any English but actually know quite a lot with can be quickly activated; they’re not real beginners.

Elementary students aren’t beginners and are able to communicate in a basic way. They can string some sentences together, construct a simple story, or take part in simple spoken interactions.

Pre-intermediate students haven’t yet achieved intermediate competence, which involves greater fluency and general comprehension of some general authentic English.

However, they’ve come across most of the basic structures and lexis of the language. Upper-intermediate students, have the competence of intermediate students plus an extended knowledge of grammatical construction and skill use.

However, they may not have achieved the accuracy or depth of knowledge their advanced colleagues have acquired, and as a result are less able to operate at different levels of subtlety.

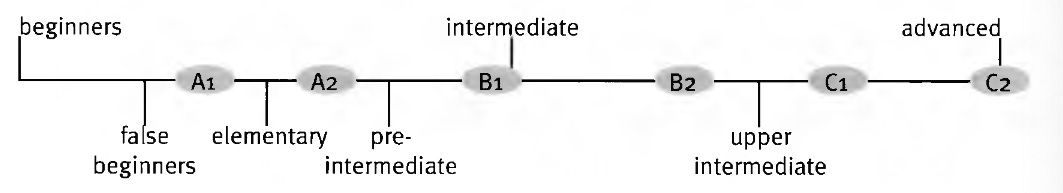

In recent years, ALTE and the Council of Europe have worked to define language competency levels for learners of a number of different languages.

The result is the Common European Framework, a doc setting out in detail what students can do at various levels, and a series of ATLE levels ranging from A1, roughly equivalent to elementary level, to C2, very advanced.

The following diagram shows the different levels in sequence:

What do these levels mean for the students? If they’re at level B1, for ex, how can their abilities be described? ALTE has produced can do statements to try to make this clear, as the ex below for the skill of writing demos, A1 is at the left, C2 at the right.

ALTE levels and can do statements, alongside the more traditional terms we have mentioned, are being used increasingly by course book writers and curriculum designers, not only in Europe but across much of the language-learning world.

ALTE ‘can do’ statements for writing:

Can complete basic forms and write notes including times, dates, and places.

Can complete forms and write short simple letters or postcards related to personal info.

Can write letters or make notes on familiar predictable matters.

Can make notes while someone’s talking or write a letter including non-standard questions.

Can prepare/draft pro correspondence, take reasonably accurate notes in meetings or write an essay which shows an ability to communicate.

Can write letters on any subj and full notes of meetings or seminars with good expression or accuracy.

However, two points are work making: the ALTE standard are only one way of measuring proficiency. ESL standards were developed by the TESOL org in the US, and many exam systems have their own level descriptors.

We also need to remember students’ abilities within any particular level may be varied too, ie. They may be much better at speaking than writing, for ex.

If we remind ourselves terms such as beginner and intermediate are rough guides only, unlike ALTE levels, they don’t say exactly what the students can do, then we’re in a position to make broad generalizations about the different levels:

Beginners - success’s easy to see at this level and easy for the teacher to arrange, but then so is failure! Some adult beginners find language learning’s more stressful than they expected and reluctantly give up.

However, if things are going well, teaching beginners can be incredibly stimulating. The pleasure of being able to see our part in our students’ success is invigorating.

Intermediate students - success is less obvious at intermediate level, students already having achieved a lot, but they’re less likely to be able to recognize an almost daily progress.

On the contrary, it may sometimes seem to them they don’t improve much or fast anymore. We often call this the plateau effect, and the teacher has to make strenuous attempts to show students what they still need to learn without being discouraging.

One of the ways of doing this is to make the tasks we give them more challenging, and to get them to analyze language more thoroughly.

We need to help them set clear goals for themselves so they have something to measure their achievement by.

Advanced students - students at this level already know a lot of English. There’s still the danger of the plateau effect, even if it’s higher up, so we have to create a class culture where students understand what still has to be done, and we need to provide good, clear evidence of progress.

We can do this through a concentration not so much on grammatical accuracy, but on style and perceptions of, for ex, appropriacy, using the right language in the right situation, connotation, whether words have a negative or positive thing, for ex, and inference, how we can read behind the words to get a writer’s true meaning.

In these areas, we can enable students to use language with more subtlety. It’s also this level, esp, we have to encourage students to take more responsibility for their own learning.

Although many activities can clearly be used at more than one level, designing newspaper front pages, writing radio commercials, etc, others aren’t so universally appropriate.

With beginners, for ex, we won’t suggest abstract discussions or the writing of discursive essays. For advanced students, a drill where students repeat in chorus and individually, seen in a CH below, focusing on simple past tense questions will almost certainly be inappropriate.

Where a simple role-play with ordinary info questions, ‘What time does the next train to London leave?’, ‘What’s the platform for the London train?’, etc, may be a good target for beginners to aim at, the focus for advanced students will have to be richer and more subtle, for ex, ‘What’s the best way to persuade someone of your opinion in an argument?’, ‘How can we structure writing to hold the reader’s attention?’, ‘What different devices do English speakers use to give emphasis to the bits of info they want you to notice’?

Another obvious difference in the way we teach different levels is language. Beginners need to be exposed to fairly simple grammar and vocab which they can understand.

In their language work, they may get pleasure, and good learning, from concentrating on straightforward questions like ‘What’s your name?’, ‘What’s your telephone number?’, ‘Hello’, ‘Goodbye’, etc.

Intermediate students know all this language already and so we’ll not ask them to concentrate on it. The level of language also affects the teacher’s behaviour.

At beginner levels, the need for us to rough-tune our speech is very great: we can exaggerate our voice tone and use gesture to help us to get our meaning across, but at higher levels, such extreme behavior isn’t so important.

Indeed, it’ll probably come across to the students as patronizing. At all levels, teachers need to ascertain what students know before deciding what to focus on.

At higher levels, we can use what the students already know as the basis for our work; at lower levels we’ll for ex, always try to elicit the language, that is, try to get the language form the students rather than giving it to them, we’re going to focus on.

This way we know whether to continue with our plan or whether to amend it then and there due to students, perhaps, knowing more than expected.

Educational and cultural background - We’ve already discussed how students at different ages present different characteristics in the class.

Another aspect of individual variation lies in the students’ cultural and educational background. Some children come from homes where education is highly values and parental help readily available.

Other children may come from less supportive backgrounds with no such backup on offer. Older students, esp adults, may come from a variety of backgrounds and as a result have very different expectations of what teaching and learning involves.

Where students have different cultural backgrounds from the teacher or from each other, they may feel differently from their classmates about topics in the curriculum.

They may have different responses to class practices from the ones the teacher expected or the ones which the writers of the course book they’re using had anticipated.

In some educational cultures students are expected to be articulate and question, or even challenge their teachers, whereas in others, students’ quietness and modesty are more highly prized.

Some educational cultures find learning by rote, memorizing facts and figures, more attractive than learning by doing, where students are involved in project work and experimentation in order to arrive at knowledge, and worth remembering even where students all live in the same town or area, it’s often the case they come from a variety of cultural backgrounds.

Multilingual classes, where students come from different countries and therefore have different mother tongues, are the norm, esp in private language schools, in English speaking countries such as Britain, U.S., Aus, etc.

As teachers, we need to be sensitive to different backgrounds. We need to be able to explain what we’re doing and why; we need to use material, offer topics and employ teaching techniques which, even when engaging and challenging, will not offend anyone in the group.

Where possible, we need to be able to offer different material, topics and teaching techniques, at different time to suit the different individual expectations and tastes.

The importance of student motivation - A variety of factors can create a desire to learn. Perhaps the learners love the subj they’ve chosen, or maybe they’re simply interested in seeing what it’s like.

Perhaps, as with young children, they happen to be curious about everything, including learning. Some students have a practical reason for their study:

they want to learn an instrument so they can play in an orchestra, learn English so they can watch American tv or understand manuals written in English, etc.

This desire to achieve some goal’s the bedrock of motivation and if it’s strong enough, it provokes a decision to act. For an adult this may involve enrolling in an English class.

For a teen it may be choosing one subj over another for special study. This kind of motivation, which comes from outside the class and may be influenced by a number of external factors such as the attitude of society, family and peers to the subj in question’s often referred to as extrinsic motivation, the motivation students bring into the class from outside.

Intrinsic motivation is the end generated by what happens inside the class; this could be the teacher’s methods, the activities students take part in, or their perception of their success or failure.

While it may be relatively easy to be extrinsically motivated, which’s to have a desire to do something, sustaining the motivation can be more problematic.

As students we can become bored, or we may find the subj more difficult than we thought. One of the teacher’s main aims should be to help students to sustain their motivation. We can do this in a number of ways.

The activities we ask students to take part in will, if they involve the students or excite their curiosity, and provoke their participation, help them to stay interested in the subj.

We need to select the appropriate level challenge so things are neither too difficult or easy. We need to display appropriate teacher qualities so students can have confidence in our abilities and professionalism, see CH2.

We need to consider the issue of affect, how the students feel about the learning process. Students need to feel the teacher really cares about them; if students feel supported and valued, they’re far more likely to be motivated to learn.

One way of helping students to sustain their motivation’s to give them as far as feasible, some agency, a term borrowed from social sciences, which means students should take some responsibility for themselves, and they should, like the agent of a passive sentence, be the ‘doers’ in class.

This means they’ll have some decision-making power over the choice of which activity to do next, perhaps, or how they want to be corrected, for ex.

If students feel they’ve some influence over what’s happening, rather than always being told exactly what to do, they’re often more motivated to take part in the lesson, but however much we do to foster and sustain student motivation, we can only encourage by word and deed, offering our support and guidance.

Real motivation comes from within each individual, from the students themselves.

Responsibility for learning - if giving students agency is seen as a key component in sustaining motivation, then such agency isn’t only about giving students more decision-making power.

It’s also about encouraging them to take more responsibility for their own learning. We need to tell them unless they’re prepared to take some of the strain, their learning’s likely to be less successful than if they themselves become active learners, rather than passive recipients of teaching.

This message may be difficult for some students from certain educational backgrounds and cultures who’ve been led to believe this it’s the teacher’s job to provide learning.

In such cases, teachers will not be successful if they merely try to impose a pattern of learner autonomy. Instead of imposing autonomy, we need to gradually extend the students’ role in learning.

At first we’ll expect them, for ex, to make their own dialogues after they’ve listened to a model on an audio track. Such standard practice, getting students to try out new language’s one small way of encouraging student involvement in learning.

We may go on to try to get individual students to investigate a grammar issue or solve a reading puzzle on their own, rather than having things explained to them by the teacher.

We may get them to look for the meanings of words and how they’re used in their dictionaries, see below, rather than telling them what the words mean.

As students get used to working things out for themselves and/or doing work at home, so they can gradually start to become more autonomous.

Getting students to do various kinds of homework, such as written exercises, compositions or further study is one of the best ways to encourage student autonomy.

What’s important is teachers should choose the right kind of task for the students. It should be within their grasp, and not take up too much of their time, or occupy too little of it by being trivial.

Even more importantly than this, teachers should follow up homework when they say they’re going to, imposing the same deadlines upon themselves as they do on their students.

Other ways or promoting student self-reliance include having them read for pleasure in their own time, see in CH below, and find their own resources for language practice, in books or on the internet, for ex.

Apart from homework, teachers will help students to become autonomous if they encourage them to use monolingual leaners’ dictionaries, written only in English, but which’er designed esp for learners, and then help them to understand how and when to use them.

At earlier stages of learning, good bilingual dictionaries serve the same function and allow the students a large measure of independence from the teacher.

We’ll help students to be responsible for their learning if we show them where, either in books, online, etc, they can continue studying outside the class.

For ex, we can point them in the direction of suitable sites, if they’ve comp access, or rec good CD or DVD resources.

If students are lucky, their institution will have a self-access centre with a range of resources comprising books, including readers, newspapers, mags, worksheets, listening material, vids and dads, and comps with access to online.

Students can decide if and when to visit such centers and what they want to do there. Self-access centers should help students to make appropriate choices by having good cataloguing systems and ensuring people are on hand to help students find their way around.

However, the object of a self-access centre is students should themselves take responsibility for what they do and make their own decisions about what’s most appropriate for them.

Of course, many schools don’t have self-access centers, and even where they do, many students don’t make full use of them. This is due to not all students are equally capable of being, or wanting to be autonomous learners.

Despite this fact, we should do our best to encourage them to have agency without forcing it upon them.

CH 2 Teachers

Describing good teachers Teacher skills

Who teachers are in class Teacher knowledge

Rapport Art or science?

Teacher tasks

Describing good teachers - Most people can look back at their own schooldays and identify teachers they thought were good, but generally they find it quite hard to say why certain teachers struck them as special.

Perhaps it’s due to their personality. Possibly it’s due to having interesting things to say. Maybe the reason’s they looked as if they loved their job, or perhaps their interest in their students’ progress was compelling.

Sometimes, it seems, it was only due to the teaching being a fascinating person! One of the reason it’s difficult to give general descriptions of good teachers is different teachers are often successful in different ways.

Some teachers are more extrovert or introvert than others, for ex., and different teachers have different strengths and weaknesses.

A lot will depend on how students view individual teachers and here again, not all students will share the same opinions.

It’s often said good teachers are born, not made and it does seem some people have a natural affinity for the job, but there’re also others, perhaps who don’t have what appears to be a natural gift but who’re still effective and popular teachers.

Such teachers learn their craft through a mixture of personality, intelligence, knowledge and experience (and how they reflect on it), and even some of the teachers who’re apparently born teacher weren’t like this at the start at all, but grew into the role as they learnt their craft.

Teaching is not an easy job, but it’s a necessary one, and can be very rewarding when we see our students’ progress and know we’ve helped to make it happen.

It’s true some lessons and students can be difficult and stressful at times, but it’s also worth remembering at its best teaching can also be extremely enjoyable.

In this CH we’ll look at what is necessary for effective teaching and how it can help to provoke success - so for both students and teachers learning English can be rewarding and enjoyable.

Who teachers are in class

When we walk into a lesson, students get an idea of who we are as a result of what we look like (how we dress, how we present ourselves) and the way we behave and react to what’s going on.

They take note, either consciously or subconsciously, of whether we’re always the same or whether we can be flexible, depending on what’s happening at a particular point in the lesson.

As we’ve said, teachers like any other group of humans, have individual differences. However, one of the things perhaps which differentiates us from some other professions, is we become different people, in a way, when we’re in front of a class from the people we’re in other situations, such as at home or at a party.

Everyone switches roles like this in their daily lives to some extent, but for teachers, who we are (or appear to be) when we’re at work is esp important.

Personality

Some years ago, in prep for a presentation to colleagues, Harmer recorded interviews with a large number of teachers and students.

He asked them What makes a good teacher? and was interested in what their instant responses would be. A number of the people Harmer questioned answered by talking about the teacher’s character.

As one of them told me, I like the teacher who has his own personality and doesn’t hide it from the students so he’s not only a teacher but a person as well - and it comes through in the lesson.

Discussing teacher personality’s difficult for two reasons: in the first place there’s no one ideal teacher personality.

Some teachers are effective due to being larger than life, while others persuade through their quiet authority, but the other problem - as the respondent seemed to be saying to me in the comment above - is students want not only to see a professional who’s come to teach them, but also to glimpse the person as well.

Effective teacher personality is a blend between who re really are, and who we are as teachers. In other words, teaching’s much more than only being ourselves, however much some students want to see the real person.

We have to be able to present a professional face to the students which they find both interesting and effective. When we walk into the classroom, we want them to see someone who looks like a teacher whatever else they look like.

This doesn’t mean conforming to some kind of teacher stereotype, but rather finding, each in our own way, a personal which we adopt when we cross the threshold.

We need to ask ourselves what kind of personality we want our students to encounter, and the decisions we take before and during lessons should help to demo the personality.

This isn’t to suggest we’re in any way dishonest about who we are - teaching isn’t acting, after all - but we do need to think carefully about how we appear.

One 12-year-old interviewee Harmer talked to answered my question by saying the teacher needs to have dress sense - not always the same old boring suits and ties! (see above)

However flippant this comment seems to be, it reminds us the way we present ourselves to our students matters, whether this involves our real clothes (as in the student’s comments) or the personality we put on in our lessons.

Adaptability

What often marks one teacher out from another is how they react to different events in the class as the lesson proceeds. This is important, due to however well we have prepared, the chances are things’ll not go exactly to plan.

Unexpected events happen in lessons and part of a teacher’s skill is to decide what the response should be when they do. We’ll discuss such magic moments and unforeseen problems (see upcoming CH).

Good teachers are able to absorb the unexpected and to use it to their and the students’ advantage. This is esp important when the learning outcomes we’d planned for look as if they may not succeed due to what’s happening.

We have to be flexible enough to work with this and change your destination accordingly (of this has to be done) or find some other way to get there, or perhaps we’ve to take a decision to continue what we’re doing despite the interruption to the way we imagined things were going to proceed.

In other words, teachers need to be able to think on their feet and act quickly and decisively at various points in the lesson. When students see they can do this, their confidence in their teachers is greatly enhanced.

Teacher roles

Part of a good teacher’s art is the ability to adopt a number of different roles in the class, depending on what the students are doing.

If, for ex., the teacher always acts as a controller, standing at the front of the class, dictating everything which happens and being the focus of attn, they’ll be little chance for students to take much responsibility for their own learning, in other words, for them to have agency (see above).

Being a controller may work for grammar explanations and other info presentation, for instance, but it’s less effective for activities where students are working together cooperatively on a project, for ex.

In such situations we may need to be prompters, encouraging students, pushing them to achieve more, feeding in a bit of info or language to help them proceed.

At other times, we may need to act as feedback providers (helping students to evaluate. their performance) or as assessors (telling students how well they have done or giving them grades, etc).

We also need to be able to function as a resource (for language info, etc) when students need to consult us and at times, as a language tutor (which is, an advisor who responds to what the student is doing and advises them on what to do next).

The way we act when we’re controlling a class is very different from the listening and advising behaviour we’ll exhibit when we’re tutoring students or responding to a presentation or a piece of writing (something which is different, again from the way we assess a piece of work).

Part of our teacher personality, therefore, is our ability to perform all these roles at different times, but with the same care and ease whichever role we’re involved with.

This flexibility will help us to facilitate the many different stages and facets of learning.

Rapport

A significant feature in the intrinsic motivation of students (see above) will depend on their perception of what the teacher thinks of them, and how they’re treated.

It’s no surprise, therefore to find what many people look for when they observe other people’s lessons, is evidence of good rapport between the teacher and the class.

Rapport means, in essence, the relationship which the students have with the teacher, and vice versa. In the best lessons we’ll always see a positive, enjoyable and respectful relationship.

Rapport is established in part when students become aware of our professionalism (see above), but it also occurs as a result of the way we listen to and treat the students in our classes.

Recognizing students

One of the students Harmer talked to in his research said a good teacher’s ‘someone who knows our names’. This comment is revealing both literally and metaphorically.

In the first place, students want teachers to know their names rather than, say, pointing at them, but this is extremely difficult for teachers who see eight or nine groups a week. How can they remember their students?

Teachers have developed a number of strategies to help them remember students’ names. One method is to ask the students (at least in the first week or two) to put name cards on the desk in front of them or stick name badges on their sweaters or jackets.

We can also draw up a seating plan and ask students always to sit in the same place until we’ve learnt their names.

However, this means we can’t move students around when we want to, and students - esp younger students - sometimes take pleasure in sitting in the wrong place only to confuse us.

Many teachers use the register to make notes about individual students (Do they wear glasses? Are they tall?, etc) and others keep separate notes about the individuals in their classes.

There’s no easy way of remembering students’ names, yet it’s extremely important we do so if good rapport is to be established with individuals.

We need, therefore, to find ways of doing this which suit us best, but knowing our names is also about knowing about students.

At any age, they’ll be pleased when they realize their teacher has remembered things about them, and has some understanding of who they are.

Once again, this is extremely difficult in large classes, esp when we’ve a number of different groups, but part of a teacher’s skill is to persuade students we recognize them, and who and what they are.

Listening to students

Students respond very well to teachers who listen to them. Another respondent in my research said ‘It’s important you can talk to the teacher when you have problems and you don’t get along with the subj’.

Although there’re many calls on a teacher’s time, nevertheless we need to make ourselves as available as we can to listen to individual students, but we need to listen properly to students in lessons, too, and we need to show we’re interested in what they have to say.

Of course, no one can force us to be genuinely interested in absolutely everything and everyone, but it’s part of a teacher’s professional personality (see above) we should be able to convince students we’re listening to what they say with every sign of attn.

As far as possible we also need to listen to the students’ comments on how they’re getting on, and which activities and techniques they respond well or badly to.

If we only go on teaching the same thing day after day without being aware of our students’ reactions, it’ll become more and more difficult to maintain the rapport which’s so important for successful classes.

Respecting students

One student Harmer interviewed had absolutely no doubt about the key quality of good teachers. ‘They should be able to correct people without offending them’, he said with feeling.

Correcting students (see below in another CH) is always a delicate event. If we’re too critical, we risk demotivating them, yet if we’re constantly praising them, we risk turning them into praise junkies, who begin to need approval all the time.

The problem we face, however is while some students are happy to be corrected robustly, others need more support and positive reinforcement.

In speaking activities (see CH9), some students want to be corrected the moment they make any mistake, whereas others would like to be corrected later.

In other words, only as students have different learning styles and intelligences, so too they’ve different preferences when it comes to being corrected, but whichever method of correction we choose, and whoever we’re working with, students need to know which we’re treating them with respect, and not using mockery or sarcasm - or expressing despair at their efforts!

Respect is vital, too, when we deal with any kind of problem behavior. We could, of course, respond to indiscipline or awkwardness by being biting in our criticism of the student who’s done something we don’t approve of.

Yes this will be counterproductive. It’s the behavior we want to criticize, not the character of the student in question. Teachers who respect students do their best to see them in a positive light.

They’re not negative about their learners or in the way they deal with them in class. They don’t react with anger or ridicule when students do unplanned things, but instead use a respectful professionalism to solve the problem.

Being even-handed

Most teachers have some students which they like more than others. For ex., we’ll tend to react well to those who take part, are cheerful and cooperative, take responsibility for their own learning, and do what we ask of them without complaint.

Sometimes we’re less enthusiastic about those who’re less forthcoming, and who find learner autonomy, for ex., more of a challenge.

Yet, as one of the students in Harmer’s research said, a good teacher should try to draw out the quiet ones and control the more talkative ones, and one of her colleagues echoed this by saying a good teacher is… someone who asks the people who don’t always put their hands up.

Students will generally respect teachers who show impartiality and who do their best to reach all the students in a group rather than only concentrating on the ones who always put their hands up.

The reasons some students aren’t forthcoming may be many and varied, ranging from shyness to their cultural or family backgrounds.

Sometimes students are reluctant to take part overtly due to other stronger characters in the group, and these quiet students will only be negatively affected when they see far more attn being paid to their more robust classmates.

At the same time, giving some students more attn than others may make those students more difficult to deal with later since they’ll come to expect special treatment, and may take our interest as a license to become over dominant in the class.

Moreover, it’s not only teen students who can suffer from being the teachers pet. Treating all students equally not only helps to establish and maintain rapport, but is also a mark of professionalism.

Teacher tasks

Teaching doesn’t only involve the relationship we have with students, of course. As professionals we’re also asked to perform certain tasks.

Preparation

Effective teachers are well-prepared. Part of this prep resides in the knowledge they have of their subj and the skill of teaching, something we’ll discuss in detail below, but another feature of being well-prepared is having thought in advance of what we’re going to do in our lessons.

As we walk towards our class, we need to have some idea of what the students are going to achieve in the lesson; we should’ve some learning outcomes in our head.

Of course, what happens in a lesson doesn’t always conform to our plans for it, as we shall discuss in a below CH, but students always take comfort from the perception their teacher has thought about what’ll be appropriate for their particular class on the particular day.

The degree to which we plan our lessons differs from teacher to teacher. It’ll often depend, among other things, on whether we’ve taught this lesson or something like it before. We’ll discuss planning in detail in CH12.

Keeping records

Many teachers find the admin features of their job (taking the register, filling forms, writing report cards) irksome, yet such record keeping is a necessary adjunct to the class exp.

There’s one particularly good reason for keeping a record of what we’ve taught. It works as a way of looking back at what we’ve done in order to decide what to do next, and if we keep a record of how well things have gone (what has been more or less successful), we’ll begin to come to conclusions about what works and what doesn’t.

It’s important for professional teachers to try to evaluate how successful an activity has been in terms of student engagement and learning outcomes.

If we do this, we’ll start to amend our teaching practice in the light of exp, rather than getting stuck in sterile routines.

It’s one of the characteristics of good teachers which they’re constantly changing and developing their teaching practice as a result of reflecting on their teaching exp’s.

Being reliable

Professional teachers are reliable about things like timekeeping and homework. It’s very difficult to berate students for being late for lessons if we get into the habit (for whatever reason) of turning up late ourselves.

It’s unsatisfactory to insist on the prompt delivery of homework if it takes us weeks to correct it and give it back. Being reliable in this way is simply a matter of following the old idiom of practicing what we preach.

Teacher skills

As we’ve suggested, who we are and the way we interact with out students are vital components in successful teaching, as are the tasks which we’re obliged to undertake, but these will not make us effective teachers unless we possess certain teacher skills.

Managing classes

Effective teachers see class management as a separate aspect of their skill. In other words, whatever activity we ask our students to be involved in or whether they’re working with a board, a tape recorder or a computer, we’ll have thought of (and be able to carry out) procedures to make the activity successful.

We’ll know how to put students into groups, or when to start and finish an activity. We’ll have worked out what kinds of instructions to give, and what order to do things in.

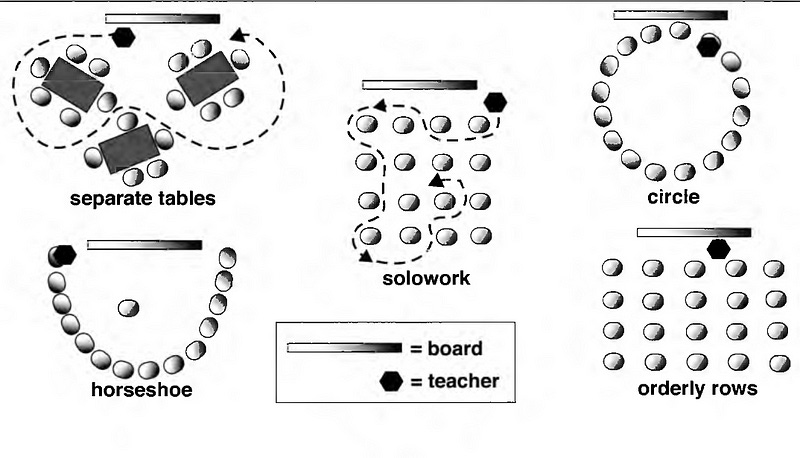

We’ll have decided whether students should work in groups, in pairs or as a whole class. We’ll have considered whether we want to move them around the class, or move the chairs into a different seating pattern (see below).

We’ll discuss class management in more detain in CH3. Successful class management also involves being able to prevent disruptive behavior and reacting to it effectively when it occurs (see below CH).

Matching tasks and groups

Students will learn more successfully if they enjoy the activities they’re involved in and are interested or stimulated by the topics we (or they) bring into the class.

Teachers, Harmer was told when conducting interviews (see above), should make their lessons interesting, so you don’t fall asleep on them!

Of course, in many institutions, topics and activities are decreed to some extent by the material in the coursebook which’s being used, but even in such situations there’s a lot we can do to make sure we cater for the range of needs and interests of the students in our classes (see above).

Many teachers have the unsettling exp of using an activity with, say two or three groups and having considerable success only to find it completely fails in the next class.

There could be many reasons for this, including the students, the time of day, a mismatch between the task and the level or only the fact which the group weren’t in the mood.

However, what such exp’s clearly suggest is which we need to think carefully about matching activities and topics to the different groups we teach.

Whereas, for ex., some groups seem happy to work creatively on their own, others need more help and guidance. Where some students respond well to teacher presentation (with the teacher acting as a controller), others are much happier when they investigate language issues on their own.

Variety

Good teachers vary activities and topics over a period of time. The best activity type will be less motivating the sixth time we ask the students to take part in it than it was when they first came across it.

Much of the value of an activity, in other words, resides in its freshness, but even where we use the same activity types for some reason (due to the curriculum expects this or due to it’s a feature of the materials we’re using), it’s important to try to ensure which learner roles aren’t always the same.

If we use a lot of group discussion, for ex., we want to be sure the same student isn’t always given the role of taking notes, rather than actually participating in the discussion themselves.

When we get students to read texts, we won’t always have them work on comprehension questions in the same way.

Sometimes they may compare answers in pairs; sometimes they may interview each other about the text; sometimes they may do all the work on their own.

Variety works within lessons, too. It’s not only children who can become bored by doing the same thing all the time.

Thus, although there may be considerable advantages in using language drills for beginner students, we won’t want to keep a drill running for half an hour due to it’d exhaust both students and teacher.

However, we may make a different kind of activity, such as a role-play, last for longer than this. A lot depends on exactly what we’re asking students to do.

Where we’re using a coursebook for a large part of the time, it’s advisable to vary the ways in which we use certain repetitive activity types.

Just due to reading comprehension exercises always look the same in a book, for ex., it doesn’t mean we always have to approach them in the same way.

We’ll discuss ways of using and adapting course books in more detail in CH11.

Destinations

When we take learning activities into the class, we need to persuade our students of their usefulness. Good activities should’ve some kind of destination or learning outcome, and it’s the job of the teacher to make this destination apparent.

Students need to have an idea of where they’re going, and more importantly, to recognize when they’ve got there. Of course, some activities, such as discussions, don’t have a fixed end.

Nevertheless, even in such circumstances, it’ll be helpful if we can make sure students leave the class with some tangible result. Which’s why a summing-up, or feedback session at the end of a discussion, for ex., is so valuable.

Teacher knowledge

Apart from the ability to create and foster good teacher-student rapport and the possession of skills necessary for organizing successful lessons, teachers need to know a lot about the subj they’re teaching (the English language).

They’ll need to know what equipment is available in their school and how to use it. They need to know what materials are available for teachers and students.

They should also do their best to keep abreast of new developments in teaching approaches and techniques by consulting a range of print material, online resources, and by attending, where possible, development sessions and teacher seminars.

The language system

Language teachers need to know how the language works. This means having a knowledge of the grammar system and understanding the lexical system:

how words change their shape depending on their grammatical function, and how they group together into phrases.

They need to be aware of pronunciation features such as sounds, stress, and intonation. These different features of the language system are explained in CH5.

Students have a right to expect teachers of the English language can explain straightforward grammar concepts, including how and when they’re used.

They expect their teachers to know the difference between the colloquial language people use in informal convo and the more formal language required in more formal settings.

They also expect teachers to be able to demo and help them to pronounce words correctly and with appropriate intonation.

When students have doubts about the language, they frequently ask their teachers to explain things. They ask ‘What’s the difference between … and…?’ or ‘Why can’t we say…?’

Sometimes the answer is clear and easy to explain, but at other times the issue is one of great complexity and even the most exp’d teacher will have difficulty giving an instant answer.

In other words, our knowledge of the language system may not be adequate for certain kinds of on-the-spot questions about subtleties.

Moreover, sometimes the question’s not especially relevant - it’s a distraction from what’s going on in the lesson. In such situations, teachers need to be able to say things like ‘That’s a very interesting question. I think the answer is X, but I’ll check to make sure and I’ll bring you a more complete answer tomorrow’ or ‘That’s a very interesting question. I don’t want to answer it now due to we’re doing something else, but you can find the answer yourself if you go to this book. We’ll discuss it tomorrow’.

Students will realize these answers are perfectly appropriate when the teacher does indeed return for the next lesson with the info they’ve promised.

This’ll demo the teacher’s knowledge of the language and reference materials, but if on the other hand, we forgot to find the info and never mention the questions again, students will gradually start to think we only don’t know enough about the language to find what we’re looking for - or we just don’t care.

Materials and resources

When students ask the kind of complicated questions mentioned above, good teachers know where to find the answers. We need to know about books and sites where such technical info is available.

However, this is quite a challenge in today’s world, where the sheer number of coursebook titles released every year can sometimes seem overwhelming, and where there’re quite a significant number of grammar books and monolingual learner’s dics (MLDs) to choose from - to say nothing of the multitude of useful sites on the internet.

No one expects teachers to be all-knowing in this respect: what colleagues and students can expect, however, is teachers know where to fin at least one good reference grammar at the appropriate level, or a good MLD, or can direct them to a library or a site where they can find these things.

If teachers are using a coursebook, students expect them, of course, to know how the materials work. Their confidence will be greatly enhanced if they can see the teacher has looked at the material they’re using before the lesson, and has worked out a way of dealing with it.

Classroom equipment

Over the last few decades the growth in different types of class equipment has been incredible. Once upon a time we only had pens, board and chalk to work with, but then along came the tape recorder, the language lab, video machines, the overhead projector, computers, data projectors and interactive whiteboards (the are all described in the appendix).

Some teachers are more comfortable with these various pieces of educational technology than others. This will always be the case. There’s no reason why everyone should be equally proficient at everything.

However, students will expect teachers should know how to use the equipment which they’ve elected to use. Learning how to use various types of equipment is a major part of modern teacher training.

However, we should do everything in our power to avoid being overzealous about the equipment itself. It’s only worth using if it can do things which other equipment or routines can’t.

The essentials of good teaching - ie rapport, professionalism, using good activities - will always be more important than the actual means of delivery.

What has changed recently, though, is students can do things they were unable to do before thanks to technical innovation.

Thus modern podcasts (downloadable listening which can be played on individual mp3 players) give students many more listening opportunities than ever before.

They can also write their own blogs (Internet diaries) and put them on the web. They can burn cds with ex.’s of their work and the materials used in class to take home when a course has finished.

They can search for a wide range of language and info resources in a way which would’ve been impossible a few years ago.

As teachers, we need to do everything we can to keep abreast of technological change in educational resources, but we should never let technology drive our decisions about teaching and learning.

We should, instead decide what our learners want to achieve and only then see what kind of techniques and technology will help them to do this.

Keeping up-to-date

Teachers need to know how to use a variety of activities in the class, of course but they also need to be constantly finding out about new ways of doing things.

A good way of learning about new activities and techniques is to read the various teachers’ magazines and journals which are available (see appendix).

There’s now a wealth of info about teaching on the internet, too. Magazines, books and sites often contain good descriptions of new activities and how to use them.

We can also learn a lot from attending seminars and teachers’ conferences, and listening to other teachers describing new activities and the successes they’ve had with them.

Two things need to be said about the various knowledges we’ve been describing. In the first place, it’s difficult for newly qualified teachers to keep everything in their heads at the same time as they struggle with the demands of a new job.

Nevertheless, as they learn their craft, we’d expect them to be hungry for as much knowledge in these areas as possible since this will make them better teachers.

Secondly, this kind of knowledge is not static, hence the need to keep up-to-date. Things change almost daily.

New books, class equipment and computer software are being produced all the time, only as teachers keep coming up with wonderful new ways of doing old things (such as grammar presentation or discussion activities).

Staying in touch with these developments can seem daunting, of course, due to the pace of change, but it’s worth remembering how deadly it’d be if things always stayed the same.

Art or science?

Is teaching language an art, then or is it a science? As this CH has shown, there’re good grounds for focusing on its almost-scientific attributes.

Understanding the language system and finding the best ways to explain it’s some kind of a scientific endeavor, esp when we continue to research its changes and evolution.

In the same way, some of the technical skills which’re required of teachers (procedures for how to do things, a constant attn to innovation in educational technology and materials design) need to be almost scientific in their rigor.

Yet teaching’s an art, too. It works when the relationship which’s created between teacher and students, and between the students in a group, is at its best.

If we have managed to establish a good rapport with a group, almost anything is possible. We’ve discussed some of the key requirements in creating such a rapport, yet behind everything we’ve said lurks the possibility of magic - or a lack of it, due to the way some teachers are able to establish fantastic rapport, or get students really interested in a new activity may be observable, but trying to work out exactly how it was done or why it happened may be more difficult.

In the same way, the instant decision-making we’ve been discussing can happen on supposedly scientific grounds, but its success, and the creativity which can be unleashed, is often the result of the teacher’s feelings or judgement at the very moment.

For as we’ve said, good teachers listen and watch, and use both professional and personal skills to respond to what they see and hear.

Good teachers have a knack of responding by doing things right, and which’s most definitely an art.

CH3 Managing the classroom

Class management Using the L1

The teacher in the class Creating lesson stages

Using the voice Different seating arrangements

Talking to students

Giving instructions Different student groupings

Student talk and teacher talk

Class management

If we want to manage classes effectively, we have to be able to handle a range of variables. These include how the class space is organized, whether the students are working on their own or in groups and how we organize class time.

We also need to consider how we appear to the students, and how we use our most valuable asset - our voice.

The way we talk to students - and who talks most in the lesson - is another key factor in class management.

We also need to think about what role, if any, there may be for the use of the students’ mother tongue in lessons.

Successful class management also involves being able to deal with difficult situations - an issue we’ll discuss in below CH.

The teacher in the class

Our physical presence can play a large part in our management of the class environment, and it’s not only appearance either (though which’s clearly an issue for the secondary students in CH2).

The way we move and stand, and the degree to which we’re physically demonstrative can have a clear effect on the management of the class.

Most importantly, the way we’re able to respond to what happens in class, the degree to which we’re aware of what’s going on, often marks the difference between successful teaching and less satisfactory lessons.

All teachers, like all people, have their own physical characteristics and habits, and they’ll take these into the class with them, but there’re a number of issues to consider which’re not only matters of personality or style and which have a direct bearing on the students’ perception of us.

Proximity

Teachers need to consider how close they should be to the students they’re working with. Some students are uncomfortable if their teacher stands or sits close to them.

For some, on the other hand, distance is a sign of coldness. Teachers should be conscious of how close they’re to their students, should take this into account when assessing their students’ reactions and should, if necessary, modify their behavior.

Appropriacy

Deciding how to close to the students you should be when you work with them is a matter of appropriacy. So is the general way in which teachers sit or stand in classes.

Many teachers create an extremely friendly atmosphere by crouching down when they work with students in pairs. In this way, they’re at the same level as their seated students.

However, some students find this informality worrying. Some teachers are even happy to sit on the floor, and in certain situations this may be appropriate, but in others it may well lead to a situation where students are put off concentrating.

All the positions teachers take - sitting on the edge of tables, standing behind a lectern, standing on a raised dais, etc - make strong statements about the kind of person the teacher is.

It’s important, therefor, to consider what kind of effect such physical behavior has so which we can behave in a way which’s appropriate to the students we’re teaching and the relationship we wish to create with them.

If we want to manage a class effectively, such a relationship is crucial.

Movement

Some teachers tend to spend most of their classes time in one place - at the front of the class, for ex., or to the side, or in the middle.

Others spend a great deal of time walking from side to side, or striding up and down the aisles between the chairs.

Although this, again is to some extent a matter of personal preference, it’s worth remembering motionless teachers can bore students, while teacher who’re constantly in motion can turn their students into tennis spectators, their heads moving from side to side until they become exhausted.

Most successful teachers move around the class to some extent. This way they can retain their students’ interest (if they’re leading an activity) or work more closely with smaller groups (when they go to help a pair or group).

How much we move around in the class will depend on our personal style, where we feel most comfortable for the management of the class and whether or not we want to work with smaller groups.

Awareness

In order to manage a class successfully, the teacher has to be aware of what students are doing and, where possible, how they’re feeling.

This means watching and listening only as carefully as teaching. This’ll be difficult if we keep too much distance or if we’re perceived by the students to be cold and aloof due to then finding it difficult to establish the kind of rapport we mentioned in CH2.

Awareness means assessing what students have said and responding appropriately. According to a writer, a colleague of his put this perfectly when he said the teacher’s primary responsibility is response-ability!

This means being able to perceive the success or failure of what’s taking place in the class, and being flexible enough (see in below CH) to respond to what’s going on.

We need to be as conscious as possible of what’s going on in the students’ heads. It’s almost impossible to help students to learn a language in a class setting without making contact with them in this way.

The exact nature of this contact will vary from teacher to teacher and from class to class. Finally, it’s not only awareness of the students which’s important.

We also need to be self-aware, in order to try to gauge the success (or otherwise) of our behavior and to gain an understanding of how our students see us.

The teacher’s physical approach and personality in the class’s one aspect of class management to consider. Another is one of the teacher’s chief tools: the voice.

Using the voice

Perhaps our most important instrument as teacher’s our voice. How we speak and what our voice sounds like have a crucial impact on class.

When considering the use of the voice in the management of teaching, there’re three issues to think about.

Audibility

Clearly, teachers need to be audible. They must be sure the students at the back of the class can hear them only as well as those at the front, but audibility can’t be divorced from voice quality: a rasping shout is always unpleasant.

Teachers don’t have to shout to be audible. Good voice projection is more important than volume (though the two are, of course, connected).

Speaking too softly or unpleasantly loudly are both irritating and unhelpful for students.

Variety

It’s important for teachers to vary the quality of their voices - and the volume they speak at - according to the type of lesson and the type of activity.

The kind of voice we use to give instructions or intro a new activity will be different from the voice which’s most appropriate for convo or an informal exchange of views or info.

In one particular situation, teachers often use very loud voices, and which’s when they want students to be quiet or stop doing something (see the next section), but it’s worth pointing out which speaking quietly is often only as effective a way of getting the students’ attn since, when they realize which you’re talking, they’ll want to stop and listen in case you’re saying something important or interesting.

However, for teachers who almost never raise their voices, the occasional shouted interjection may have an extremely dramatic effect, and this can sometimes be beneficial.

Conservation

Only like opera singers, teachers have to take great care of their voices. It’s important they breathe correctly so they don’t strain their larynxes.

Breathing properly means being relaxed (in the shoulders, for ex., and not slumped backward or forwards), and using the lower abdomen to help expand the rib cage, thus filling the lungs with air.

It’s important too teachers vary their voices throughout the day, avoiding shouting wherever possible, so they can conserve their vocal energy.

Conserving the voice is one of the things teachers’ll want to take into account when planning a day’s or a week’s work.

Talking to students

The way teachers talk to students - the manner in which they interact with them - is one of the crucial teacher skills, but it doesn’t demand technical expertise.

It does, however, require teachers to empathize with the people they’re talking to by establishing a good rapport with them.

One group of people who seem to find it fairly natural to adapt their language to their audience are parents when they talk to their young children.

Studies show they use more exaggerated tones of voice and speak with less complex grammatical structures than they would if they’re talking to adults.

Their vocab is generally more restricted, they make more frequent attempts to establish eye contact and they use other forms of physical contact. They generally do these things unconsciously.

Though the teacher-student relationship is not the same as between a parent and child, this subconscious ability to rough-tune the language is a skill teachers and parents have in common.

Rough-tuning is the simplification of language which both parents and teachers make in order to increase the chances of their being understood.

Neither group sets out to get the level of language exactly correct for their audience. They rely, instead, on a general perception of what’s being understood and what’s not, due to they’re constantly aware of the effect their words are having, they’re able to adjust their language use - in terms of grammatical complexity, vocab use and voice tone - when their listener shows signs of incomprehension.

In order to rough-tune their language, teachers need to be aware of three things. Firstly, they should consider the kind of language which students are likely to understand.

Secondly, they need to think about what they wish to say to the students and how best to do it, and thirdly, they need to consider the manner in which they’ll speak (in terms of intonation, tone of voice, etc), but these considerations need not be detailed.

To be successful at rough-tuning, all we have to do is speak at a level which’s more or less appropriate. Exp’d teachers rough-tune the way they speak to students as a matter of course.